Estranged parents don't have rights

Justice Minister rejects idea of joint custody in proposed divorce laws

Janice Tibbetts

CanWest News Service

Friday, March 28, 2003

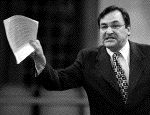

CREDIT: Tom Hanson, The Canadian Press

Martin Cauchon has come under fire because his new act will repeal

the principle that a child should have "maximum contact"

with both parents. Under the new law, judges would impose

"parenting orders." |

OTTAWA - Estranged parents have no rights when it comes to their children -- they only have responsibilities, says Martin Cauchon, the Minister of Justice.

The married father of three made the comment yesterday as he explained why he rejected the presumption of shared parenting -- or joint custody -- in his proposed new divorce laws.

"Parents have responsibilities, they don't have rights," Mr. Cauchon said under questioning from the all-party justice committee. "The starting point in each and every crisis is the best interests of the child."

Glen Cheriton, an Ottawa father who runs a support group for non-custodial parents, said the Justice Minister is trying to wipe out traditional parental rights that pre-date the Canadian government.

"The idea that parents don't have rights is a very radical concept," Mr. Cheriton said during an interview.

"The problem with the idea that parents don't have rights is that when we go to school and say we'd like to see the report cards of our kids, and they say, 'You don't have any rights,' then what do we do?

"The only reason parents want rights is so that we can take our responsibilities. The two go hand in hand."

Robbing parents of rights is also wrong because it violates a child's right to contact with both parents, Jay Hill, a Canadian Alliance member of the justice committee, said.

Mr. Cauchon was defending his proposed changes to the federal Divorce Act, which rejects the premise of "shared parenting," in which both parents would be presumed equal under the law when raising their children.

Mr. Cauchon's bill has angered fathers' groups, who lobbied hard for the key recommendation from a Parliamentary committee that there should be a presumption that both parents share the care of their children unless one parent is considered unfit.

The concept was abandoned because parents are more likely to end up in court battles if they believe they have equal access to their children, Mr. Cauchon told the committee.

"Shared parenting has created a legal presumption that we don't want," he said. "We've learned from other countries' experience."

When Australia and the United Kingdom modified their divorce laws to enshrine shared parenting, they saw a "clear spike in litigation" from estranged parents who were fighting for their perceived rights, said Virginia McRae, a Justice lawyer.

Mr. Cauchon's bill removes the contentious words "custody" and "access" from Canada's legal vocabulary and replaces them with the term "parenting orders."

Judges would impose the orders, basing their decisions on a federal list of criteria that includes the child's relationship with each parent, which parent did most of the child care before separation, and whether either has ever been violent or has a criminal record.

At least two committee members objected to judges being required to consider which parent previously did the most child care, saying it is unfair to fathers who were in traditional relationships before the divorce and worked while their wives stayed at home.

Mr. Cauchon came under fire because his new act will repeal the stated principle that a child should have "maximum contact" with both parents, which non-custodial parents have relied on since 1985 to spend time with their children.

Copyright © 2003 CanWest Interactive, a division of CanWest Global Communications Corp.