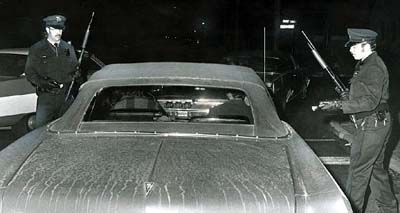

Detroit News file

1973: Police resort to brute force With guns at the ready, a uniformed police backup to the STRESS decoy unit in 1973 questions men in a car. The STRESS unit was branded a disgrace and disbanded, but not before 17 civilians were shot and killed by officers in four years. |

Police brutality comes full circle

Force has a 30-year history of abuse

|

DETROIT -- The Detroit police officers claim a teen-ager gave them three increasingly explicit confessions to the rape and murder of a woman. Yet, he turns out to have the IQ of an 8-year-old, making him unable to articulate such comments.

During six years on the force, a Detroit officer fatally shoots three people and wounds another in nine shooting incidents. Each review of the cases ends the same way: clearing the officer of any wrongdoing.

Prisoners are held in precinct cells stained with human feces. Blood, rotting food, sanitary napkins and broken glass are found in the dimly lit cells.

These incidents sound like stories from police abuses in Detroit during the 1960s, when possible witnesses to crimes were frequently locked up by police, or the 1970s, when a police decoy unit was the scourge of the black community.

But the cases, and many others like them, occurred within the Detroit Police Department in the past few years.

Two dozen former police executives, current department leaders, scholars and activists say the department's downward spiral was accelerated during 20 years of political interference by former Mayor Coleman A. Young. His successor, Dennis Archer, relied on the two chiefs he appointed to make changes to improve the department, but they failed to do so.

Following a public outcry three years ago over questionable shootings by police, the department is now being reformed under the supervision of the U.S. Justice Department.

Retired police executives, who spoke publicly for the first time, and others who have studied the department told The Detroit News that its troubles were hastened by:

![]() The failure of mayors Young and Archer to recognize that their choices for chief

were insiders lacking vision or broad police experience to reform and modernize

the department. Except for Stanley Knox, who was a precinct commander before his

promotion, the other chiefs spent nearly all of their careers doing undercover

street work with little exposure to community policing, patrol or other critical

branches of the department.

The failure of mayors Young and Archer to recognize that their choices for chief

were insiders lacking vision or broad police experience to reform and modernize

the department. Except for Stanley Knox, who was a precinct commander before his

promotion, the other chiefs spent nearly all of their careers doing undercover

street work with little exposure to community policing, patrol or other critical

branches of the department.

![]() The effort by Young to integrate the predominantly white department soured with

two botched recruitment drives in 1977 and 1986 that added nearly 1,700

officers. The department under Chief William Hart hired many unqualified and

poorly trained candidates because it lowered standards and cut training to

comply with Young's timetable to get them on the force.

The effort by Young to integrate the predominantly white department soured with

two botched recruitment drives in 1977 and 1986 that added nearly 1,700

officers. The department under Chief William Hart hired many unqualified and

poorly trained candidates because it lowered standards and cut training to

comply with Young's timetable to get them on the force.

![]() Young's appointments of cronies to key civilian department jobs, and his

promotions of others over more competent individuals, decimated morale, the

department executives said. Kenneth Weiner, a Young operative and a civilian

deputy chief, was convicted in 1991 of stealing $1.3 million from the

department.

Young's appointments of cronies to key civilian department jobs, and his

promotions of others over more competent individuals, decimated morale, the

department executives said. Kenneth Weiner, a Young operative and a civilian

deputy chief, was convicted in 1991 of stealing $1.3 million from the

department.

![]() Young's demand in 1983 that all executives from inspector up submit undated

letters of resignation shook the top command and hastened the exit of some of

the force's brightest officers. Cmdr. Philip Arreola, then a 47-year-old officer

with a law degree, went on to become police chief in Port Huron, Milwaukee,

Wis., and Tacoma, Wash. He now works for the U.S. Justice Department in Denver.

Young's demand in 1983 that all executives from inspector up submit undated

letters of resignation shook the top command and hastened the exit of some of

the force's brightest officers. Cmdr. Philip Arreola, then a 47-year-old officer

with a law degree, went on to become police chief in Port Huron, Milwaukee,

Wis., and Tacoma, Wash. He now works for the U.S. Justice Department in Denver.

![]() Archer's determination not to repeat Young's mistakes made him adopt a hands-off

approach to the department until it was too late. The mayor put his faith in

Chiefs Isaiah McKinnon and Benny Napoleon, neither of whom acted upon signs of

trouble.

Archer's determination not to repeat Young's mistakes made him adopt a hands-off

approach to the department until it was too late. The mayor put his faith in

Chiefs Isaiah McKinnon and Benny Napoleon, neither of whom acted upon signs of

trouble.

In addition to 47 people shot by police under the administrations of McKinnon and Napoleon, at least 18 prisoners, some arrested on minor charges, died suddenly in police department lockups between 1992 and 1999. In an interview with The News in 2001, Napoleon said he did not know Officer Eugene Brown had shot four people in five years. "It's not something we're capable of flagging at this time," he said.

![]() The failure of the department to adopt any system to determine whether

performance goals in the precincts and in the central command were being met.

There was no risk-management system in place to identify potential problems and

root out rogue cops. From 1987 to 2000, the city paid $123 million to settle

lawsuits stemming from complaints of police misconduct.

The failure of the department to adopt any system to determine whether

performance goals in the precincts and in the central command were being met.

There was no risk-management system in place to identify potential problems and

root out rogue cops. From 1987 to 2000, the city paid $123 million to settle

lawsuits stemming from complaints of police misconduct.

National reputation

In the years after the 1967 riot, the department, under two chiefs brought in from outside, Patrick Murphy and Johannes Spreen, enjoyed a national reputation for superior training and a crack homicide section that solved more than 80 percent of its cases.

But Young -- using the killings of African-Americans by the STRESS (Stop the Robberies, Enjoy Safe Streets) decoy unit as a central campaign issue -- was elected mayor in 1973 and, three years later, picked the little-known Bill Hart to lead the department. He became the longest-serving chief in Detroit history, holding the post until 1991.

Despite winning recognition early in his tenure for community policing efforts that included expanding the neighborhood mini-station network, Hart's career ended in disgrace as he was indicted and convicted of stealing $1.3 million from a police undercover fund. He spent seven years in prison.

Other problems with the department's leadership developed after Young became mayor. John Tsampikou and Jerry Miller were two commanders who refused to submit the undated letter of resignation that Young required of the department's top officers.

"The letter changed everything," Tsampikou said. "It was clear the mayor was calling the shots and your careers were in his hand."

Another Young demand, that all executives sell up to $1,000 worth of campaign tickets or pay for them, further demeaned their professional standards, the retired officers said.

For most of the 1980s, the department was adrift, the former department executives said. "In my last seven years, no one ever called me up to ask what I was doing about crime in my precinct," Tsampikou recalled.

At the same time, violent crime was skyrocketing in Detroit. The city had the highest homicide rate in the nation in 1983 and 1984. It was reminiscent of 1974, when a similar jump in the murder rate earned Detroit the moniker Murder City.

A person who answered the phone at Hart's home in New Jersey said he would not comment.

Hart was succeeded by Stanley Knox, who in his two years as chief, put more officers on the streets and did a better job of supervising them, but he did not address the deep-seated personnel problems on the force, retired Cmdr. Ronald Vasiloff said.

Detroiters only

Jerry Miller, who recently retired as chief of corporate security for Chrysler Corp., knows the Detroit Police Department's history as well as anyone.

He worked in precincts. He spent time in the training academy, the recruiting section, as well as the analysis and planning section.

Miller said that when Young ordered the department to hire 700 officers in 1977, the mayor further complicated the process by requiring the department to hire only Detroiters.

"By limiting the search to Detroit residents, the mayor drastically shrunk the pool the department could choose from," Miller said.

Vasiloff, who was Hart's top aide for four years, was with the chief when Young ordered the hirings in 1977. Vasiloff said Young called Hart and asked how many recruits were processed and ready to go.

Hart called the recruiting section. The officer in charge inflated the numbers, telling Hart they had 1,000 candidates. The chief called Young and told him they had 1,000 ready to go.

"Hire them," Young told Hart, who was flabbergasted.

"No one told the mayor only 250 were actually processed and were viable candidates," Vasiloff said.

Retired Insp. Walter Schnabel, who worked as an investigator in the recruiting section during the massive officer recruiting drives, said the established process was turned upside down. The regulations dictated that each applicant clear a thorough background check that included an interview in their homes before they were brought in for further discussions.

In 1977, panels of two sergeants and a police officer interviewed candidates first, then followed up with abbreviated background checks. The home interviews were discontinued.

Also that year, one class of 47 recruits flunked the state-mandated certification test for police officers, registering the lowest score ever recorded by any police recruits in the state.

Less than a year later, two rookie officers shot and killed an unarmed man in traffic stop. Eight others were involved in shooting incidents, including three who accidentally shot themselves with their department-issued handguns.

Schnabel, a sergeant during the second recruiting drive in 1986, said he worked every day, including 10 hours on Sundays, processing applicants. Many of the candidates were politically connected and were quickly eased through the process, he said.

Fatal force, roundups

Two of the crucial issues in the U.S. Department of Justice's investigation that led to its oversight of Detroit police involved the use of fatal force by officers and the homicide section's illegal practice of rounding up people and holding them until someone cooperated or confessed to murders.

In both those abuses, the department was forewarned of the practices years before the Justice Department stepped in, according to the retired commanders.

Miller recalled serving on a department board of review investigating a killing by an officer in 1986. As a result of that investigation, the three-member board of senior officers made a series of written recommendations for changes in the department's policies on fatal force. The recommendations included the adoption of non-lethal weapons.

"They were ignored and never went anywhere," Miller said.

Another major part of the Justice Department's case against Detroit police -- the indiscriminate roundups of potential witnesses until someone confessed or cooperated -- came to light in a 1997 lawsuit.

The case involved a whistleblower lawsuit in which a homicide investigator accused the commander of the unit, Insp. Joan Ghougoian, of coercing confessions by making false promises to suspects. Vasiloff and two other ranking executives were appointed by McKinnon to investigate the matter. From testimony of homicide officers, the panel learned homicide investigators routinely locked up witnesses without charges for indefinite periods of time.

"We asked one investigator, who is still in that section, why they were ignoring the department rules on holding witnesses without charges," Vasiloff said.

Vasiloff said the investigator replied: "Those rules are for the rest of the department. They don't apply to the Homicide Section."

In its report to McKinnon, the panel made several recommendations to curb the abuse of witnesses, but nothing came of them, Vasiloff said.

Former precinct commander Mack Douglas said for years the McKinnon-Napoleon administration turned a blind eye to serious problems.

"The mass arrest of witnesses, we all wondered how that was allowed to go on. How long can property go missing from the evidence room without anyone asking what's wrong?" Douglas asked.

Napoleon rejected criticism that he didn't take steps to track rogue police officers. He set up a computer system to do the job, but the city would not give him the money to hire people to input officers' data from tens of thousands of paper records into the computer system.

And Napoleon said training was a priority in his department, to the point that the Michigan Justice Training Commission complained he spent too great a share of available state funds on training. Napoleon said he made it mandatory that all managers attend either the FBI National Academy or the Northwestern University School of Police Staffing Command.

Archer, who appointed McKinnon and Napoleon, acknowledged that he made it a point not to interfere with the department.

"I am not a police officer. I didn't know how departments were run, and I trusted the judgment of the leadership because I trusted the command folks," he said. Archer said he would have intervened if he had been alerted to the unwarranted shootings of civilians by officers.

Archer remembered turning over to McKinnon a report in 1993 by then-Deputy Chief Daniel McKane and Vasiloff, the retired commander, that identified major problems with the department. The topics of their report could be used as a guide to why, in 2003, the department is beset by police misconduct: Lack of Direction. Poor Use of Resources. Politicization of the Department. Corruption. Lack of Training. Poor Labor-Management Relations.

"I indicated to Ike that I wanted it implemented within our financial ability, to have a better police department," Archer said. "I presumed he got it done."

None of the major changes recommended by the report was implemented.

You can reach Norman Sinclair at (313) 222-2034 or nsinclair@detnews.com.