|

Domestic violence plagues Russia

|

||

|

||

Thursday, 26 August, 2004, 15:50 GMT 16:50 UK

A female therapist talks Svetlana gently through her anxieties, at a crisis centre in central Moscow.

In this cramped office, specialists are helping Svetlana rebuild her self-esteem, shattered by years of abuse.

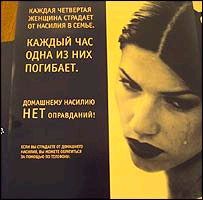

A Russian woman dies every 40 minutes from domestic violence

|

''He forced me into the car and drove me out to the country. Then he tied me to a bed and beat me,'' Svetlana says, staring down at her hands in her lap.

"As a minimum, he raped me. As a maximum he was trying to kill me. He told me if I tried to get help, I would die."

Svetlana endured her husband's persistent violence in silence, too ashamed to tell friends what she was going through. She says the police saw her suffering as a private, family affair.

"I called the police once when I thought I couldn't cope alone any more. I really needed help," she recalls. "But when they came - I was there in tears, and all my clothes were ripped - they just told me it was all my fault."

Svetlana is not alone. Police statistics show that one woman is killed by her husband or partner in Russia every 40 minutes. Women's groups believe the true figures are far higher.

Drink

Across Moscow, the city authorities stage a fair to mark family day. They're celebrating a much vaunted institution here.

But in a small corner of the fair, hidden among the sweet stands, a group of women is trying to drag that hidden horror into the public spotlight. They call on passers-by to plunge their hands into paint and add their prints to a banner headed "Stop domestic violence".

|

" She would have had to file a complaint about the beating,

but I'm her husband. She loves me, so what can she do? "

Sasha

|

"If you think you're only normal if you're married with children, then you'll do anything you can to keep that status. If you lose it - you've failed as a woman and a mother," she explains. "To avoid that, many women here will suffer and suffer - and suffer."

In one of Moscow's poorer suburbs, policeman Vladimir Vysotsky sets out on his daily beat. Vladimir says the vast majority of his work is dealing with "saucepan brawls" - police slang for domestic violence.

"It happens here almost every day," Vladimir says. "And why do most scandals start? Because the husband drinks. Why does he drink? Because he has problems with his job - and with money."

Irina and Sasha are one of Vladimir's regular calls. Irina was sacked from work recently when she turned up covered in bruises once too often.

"I used to hit her, when I got drunk," Sasha admits frankly sitting at his kitchen table in a filthy vest. "But it doesn't happen anymore. The police would sometimes take me in - but only for the drinking.

"She would have had to file a complaint about the beating, but I'm her husband. She loves me, so what can she do?"

Recognition

Irina sits silently, until her husband leaves the room.

Larissa would like to see a better education campaign

|

"Of course I wanted to leave him," she says. "But where could I go?"

There are no refuges in Russia; nowhere safe for women like Irina to run to.

Over on the far smarter side of town, there are signs that some things are improving.

ANNA is a cosy day centre set up on international grant money as a first point of call for victims of abuse.

Russia has crisis hotlines now too, and non-governmental organisations run group sessions and offer free advice in a growing number of cities.

"There is certainly much more recognition of the problem than there was 10 years ago," says ANNA's Larissa Ponarina. "But it's not enough."

Larissa believes Russia needs a major education drive to help it wake up to the problem.

"At least if society and the police were educated, we'd have fewer people killed," she says. "Fourteen thousand deaths a year is terrible. We have to try to do our best to reduce the number of people close to death, by intervention at an early stage."

New life

Sipping a coffee after her therapy session, Svetlana announces she has just secured her first ever job and a vital new sense of independence.

"I've started to feel again," Svetlana says, "To remember what happened, but to stop it hurting any more. I've started to live again."

Svetlana's own strength stopped her becoming just another statistic. But she still can't escape her ex-husband entirely.

Dima knows exactly where she lives and he has started to call again. The confidence Svetlana fought so hard to recover remains extremely fragile.