|

By Robert Hodierne

In Arlington, Virginia |

Monday, 6 September, 2004, 14:32 GMT 15:32 UK ![]()

As the presidential election approaches, the BBC is broadcasting the reflections of commentators around the US. This week Robert Hodierne, who edits publications about and for the US military, considers the changing role played by women in the armed forces.

The Humvee truck gives soldiers little protection from attack

|

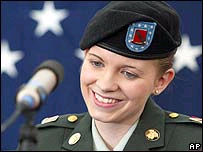

If you met Teresa Broadwell at a dance club, you would probably think the 20-year-old, 5'4" (1.62m), 112-pound (51kg) woman was - well, it is not politically correct to use this term - but you would think she was cute.

Perky even.

But if you had met her one dark night last October on a nasty little side street in Karbala, Iraq and, if you had been an Iraqi toting an AK-47, well then, quite simply, you would most likely be dead.

This young woman with the improbably vivid turquoise contact lenses - who calls herself "Little-bitty-Teresa" - this kid with the girl-next-door charm is a decorated combat hero.

When her armoured Humvee came racing to the rescue of fellow military police troops - and let's put special emphasis on fellow - when her Humvee came tearing around the corner, there were already three soldiers sprawled dead in the street.

Bullets and rocket-propelled grenades criss-crossed the foggy road, turning it into a vicious killing zone.

Broadwell, standing on tiptoes in the open, oh-so-terrifyingly exposed turret of her Humvee, opened up with her light machine gun.

Medal

She fired off short, controlled bursts, just like she had been trained. The guys whose lives she saved that night say she killed at least 20 Iraqis.

But here is the truly startling thing. She was not the only woman hero that night.

Misty Frazier - who had been trained as a medical aide and thought she would spend her military hitch in the safety of a hospital - she ended up in another of those military police Humvees as a combat medic.

And when the Iraqis opened fire and MPs began falling, Frazier leapt from her Humvee and ran from one wounded soldier to another.

|

" So far in this go-round in Iraq, 25 women have been

killed "

|

And so did three other women that night. Five women decorated for combat bravery in one nasty firefight. That has never happened before in the history of the US military.

These women, largely unheralded, are the new face of feminism in the US military.

Not the first place you would think to look for it - but American women in uniform are staging a quiet, almost unnoticed revolution.

This revolution is redefining the role women will play in future wars.

But what's more, they are demonstrating that the limits confronting women - which we had once assumed were immutable biological facts of life - are not so immutable after all.

Damsel

They are too weak, they nurture, they do not kill, they are not brave enough.

Tell that to the Iraqis down range from Teresa Broadwell.

But it is a quiet, almost unnoticed change. For most people, the female face of an American soldier remains Private Jessica Lynch.

Lynch, as you will recall, was captured in the early days of the war when her supply convoy got lost and ambushed. And then, in a much publicised raid, American commandos snatched her from the Iraqi hospital where she was being held.

Private Jessica Lynch claimed she had done nothing heroic

|

With the full force of the Pentagon publicity machine behind it, the Lynch story played big.

After all, she was a fair damsel in distress rescued by daring men. There is a storyline the public can easily understand.

But if you want to make a soldier mad, bring up Lynch.

Lynch angers many soldiers - men and women - because, in their view, she was not a hero.

She and her buddies screwed up. They were supply soldiers, not trained in the real ways of combat.

When they were ambushed, most of their rifles jammed.

Ingenue

It makes soldiers angry that she had all that attention, all those TV appearances, the million-dollar book deal.

Forget that Lynch was set up by the brass for her role as ingenue.

She was shamelessly exploited - first by the military, who wanted a feel-good story at a time when the war was staggering a bit, then by the media - we are always looking for easy storylines.

But, while Lynch plays to the helpless-girl-in-need-of-rescue stereotype, there are other women who play against that image.

|

" In many ways the military is a good deal for women "

|

The most shocking images coming out of Abu Ghraib feature Private Lynndie England.

There she is, mugging with dead bodies, leering at naked prisoners and leading one around on a dog leash.

Nurturers indeed.

Turns out the women can be just as perverse as the men. Who would have known?

Feminism

And, of course, we must not forget that those MPs at Abu Ghraib were under the command of Brigadier General Janis Karpinski.

Together, those women present another, uglier image of the military's new feminism.

What is a bit strange here, though, is how little attention has been given to Teresa Broadwell and Misty Frazier and dozens of other women doing similar things.

You see, their existence is kind of a secret. In America, it is against the law for women to hold ground combat jobs.

But if that is so, you may well ask, how did Little-bitty Teresa wind up on the business end of a light machine gun in Karbala?

A little background is in order.

Women can hold lots of other non-combat jobs. About 17% of the American armed forces are women.

They seem to join for about the same reasons the men do - patriotism, a steady job, money for a college education, a ticket out of a crummy inner-city neighbourhood or out of a boring town in some rural backwater.

In the civilian job market, American feminists point to the progress women have made.

Why, 20 years ago women earned only 65 cents for every dollar a man earned.

Today that has inched up to 75 cents for every dollar.

Segregated

But get this - in the military, women are paid the same as the men. Except at the very highest ranks, they get promoted at the same rates and they re-enlist at the same rates. In many ways, the military is a good deal for women.

Except women cannot be in the infantry, they cannot drive tanks, they cannot be in special forces or other elite combat units.

Women are segregated into so-called support jobs, where the adventure, if it comes - like it did for Jessica Lynch - comes by accident.

And that does limit careers.

The US military police are not considered combat soldiers

|

While 17% of the force is female, only 4% of the generals are.

After the first Gulf War there was a muted debate in this country about women in combat.

It has never been a high priority for the activists in the feminist movement. They are more interested in jobs in the board room than jobs on the front lines.

Support

Within the military itself there is an odd split.

A number of surveys show that troops generally support the idea of allowing women in combat.

But the leadership - older, more conservative, overwhelmingly male - has never pushed for it.

But neither, to be fair, have they prevented the line between combat jobs and non-combat from becoming blurred.

As an example of just how bizarre this dividing line has become, women can fly combat aircraft.

One of the women who has pushed the line the hardest has just been assigned to lead an Air Force fighter squadron.

That is a first.

The woman in question, Lieutenant Colonel Martha McSally, has a lot of firsts.

She was the first woman to fly in combat. She was also the woman who sued the Defense Department so she wouldn't have to wear the black, head-to-toe abaya while stationed in Saudi Arabia.

She won.

|

" There are jobs held by women that do not seem any

less dangerous than being in the infantry "

|

So why, then, the continued ban on women from ground combat jobs?

There is the physical strength part of it.

A typical field pack weighs in at over 100 pounds (45kg). Not many women can carry that much weight.

Rape

And in fairness, a lot of the women, including some of the MPs with medals on their chests, do not think they could hack it in the infantry. Too physically demanding.

And then there is the rape issue.

In the first Gulf War, two women were captured by the Iraqis. One of them was raped.

We should not put our women in that sort of danger, the argument goes.

Finally, there is this argument: The American people will not tolerate their daughters being killed in war.

During the dozen or so years that America fought in Vietnam, 55,000 of our sons were killed. Eight of our daughters were.

In the first Gulf War, five women were killed. So far in this go-round in Iraq, 25 women have been killed and I have not heard a peep from anyone about that.

I suppose this can be viewed as some kind of twisted social progress.

Like the MP jobs, there are other jobs held by women that do not seem any less dangerous than being in the infantry.

One morning last winter a small convoy of American vehicles sped into Fallujah to disarm a mine spotted in the middle of an intersection.

Ambush

The paratroopers set up a perimeter around the intersection. From a rooftop nearby, four rounds were fired in the general direction of the soldiers.

There were no civilians within two blocks. It smelled like an ambush.

In that tense scene, the explosives expert the soldiers had brought along began the unenviably touchy job of walking out in the open and detonating the mine.

Viewed from a distance, the baggy fatigues, bulky body armour and Kevlar helmet obscured the fact that the expert was a woman: Staff Sergeant Melissa Kennedy, 28-years-old.

If she screwed this up, she would be pulverised by a mine powerful enough to blast the hell out of 60 tons' worth of tank.

Kennedy placed her explosives and, with every eye on her, she sauntered away with a casual, steady, this-don't-scare-me swagger that caused one of the soldiers to say, admiringly and without any evident irony: "She's got balls."

I asked Kennedy about the line dividing combat jobs from non-combat jobs, jobs that women can legally hold.

She drew a line in the dusty street with the toe of her beat-up combat boot.

"Show me the line," she said.

Her voice had real bite to it. She rubbed the line out with her boot and repeated, "Show me the line."

State Of The Union is broadcast on BBC Radio 4 on Fridays at 2050 BST and repeated on Sundays at 0850 BST.