| Don Butler | |

| The Ottawa Citizen |

|

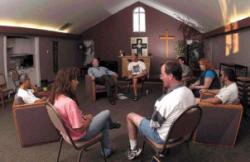

| CREDIT: Stuart Davis, The Vancouver Sun |

| At the Ferndale Institution, a minimum-security prison in Mission, B.C., prisoners and volunteers meet to talk about their lives and the values that are changing the way they think and act. |

IN MISSION, B.C. - It's a warm spring evening, and I am sitting in a circle with seven murderers. We are perched on chairs in the chapel of Ferndale Institution, a minimum-security prison in Mission, in British Columbia's Fraser Valley. My ominous companions, each serving a life sentence for murder, are members of Ferndale Advocates for Victim Offender Reconciliation, a group of prisoners and community volunteers that meets every Wednesday night to talk about their lives and the values that are changing the way they think and act.

One circle member killed a jewelry-store owner during a robbery, more than 20 years ago now. Another murdered a taxi driver in 1992. A third is a sad-faced young man notorious for his role in the death of 14-year-old Reena Virk, a vicious gang killing that shocked the nation in 1997.

Yet despite their brutal crimes, none of these men comes close to matching my mental image of a murderer. Indeed, the first two I encounter outside the chapel are so unthreatening that I wrongly assume they are community volunteers.

During the circle, one man talks about peacefully solving a recent conflict with a prison guard. "I left there, and I felt so good," he says, with visible emotion. "I felt healed, I felt heard." Another, whose crimes include sexual offences, recalls how he felt after receiving a hug from victims of sexual assault who spoke to inmates. "I hadn't been touched in 14 years," he says quietly. "I realized I was still human."

Others discuss a day-trip they took with a community volunteer to Vancouver to see the Dalai Lama, their eyes shining with enthusiasm.

As they talk with honesty and candour about their lives, the men strike me as sensitive and compassionate -- not traits commonly associated with murderers. Above all, they seem human, struggling with the same foibles and emotions that afflict us all.

The main agent of this apparent alchemy is restorative justice, a set of values, principles and processes that has quietly, and with little public notice, been influencing the way governments around the world think about crime and punishment. It is now widely used both to divert cases from the courts, and as part of the sentencing process for more serious crimes.

"I do believe it's one of the few big ideas in criminal justice," says David Daubney, co-ordinator of the sentencing review team at the Department of Justice. "It's an important movement with huge benefits," agrees Julian Roberts, a criminologist at the University of Ottawa. Kent Roach, a University of Toronto law professor, calls it "a genuine and powerful new idea about justice and crime."

For those who equate justice with courts, prisons and punishment -- as most of us still do -- the ideas behind restorative justice may seem as improbable as the proposition that the murderers in Ferndale's Wednesday-night circles aren't necessarily moral monsters. And in truth, there is still much debate and skepticism about them.

Some argue restorative justice works only with young offenders and minor crime, and is inappropriate for repeat offenders and those who commit violent crimes. Others worry that it represents a form of privatized justice, threatens to bring more people into the state's net of social control and undermines the principle that justice should be conducted in public, not private, forums. And there are fears that restorative justice processes could lead to abuse of both offenders and their victims.

|

| CREDIT: Bruno Schlumberger, The Ottawa Citizen |

| The influence of restorative justice, according David Daubney, co-ordinator of the sentencing review team at the Department of Justice, has helped to reduce Canada's traditionally high adult incarceration rate from about 133 per 100,000 population in the mid-1990s, the fourth-highest among Western democracies, to around 109 today, which places us ninth. |

The restorative approach conceives of justice quite differently than the retributive philosophy that dominates our thinking. Instead of focusing on crime as a violation of the law and the state, restorative justice sees it as a violation of people and relationships. While the criminal justice system is primarily concerned with establishing guilt and punishing offenders, restorative justice begins with victims of crime and their needs.

To repair the harm done to victims, it encourages offenders to learn about the consequences of their crimes and the people they have victimized. It seeks to annul the state monopoly over justice by involving members of the community affected by the offender's wrongdoing.

In stark contrast to the criminal justice system, which sidelines victims and offers few incentives to encourage criminals to take responsibility for their crimes, restorative processes give offenders the chance to meet the people they have harmed, offer apologies and make amends, often through restitution or community service.

The impact can sometimes be extraordinary, both for victims and for offenders.

"These experiences, from our anecdotal and research experience, are often transformational," says Jane Miller-Ashton, the former executive director of the Correctional Service of Canada's restorative justice and dispute resolution unit. "Victim and offender walk away with much more than they expected."

- - -

The modern restorative justice movement began 30 years ago, when two young men who went on a vandalism rampage in Elmira, Ont., were ordered by a judge to meet and make amends to their victims as part of their sentence, which also included a fine and probation.

Since then, restorative ideas have become a global phenomenon. Today, there are thousands of restorative justice projects in more than 50 countries.

In Canada, hundreds of restorative initiatives operate in communities, in prisons and in concert with the court system. Last year, the Law Commission of Canada released a report that concluded that restorative processes could be effective in dealing with all types of crime and conflict. The government is expected to formally respond to the report this fall.

In recent years, restorative justice ideas have infiltrated criminal law processes and institutions in a number of ways:

- Restorative thinking heavily influenced the new Canadian Youth Justice Act. Since it came into force in May 2003, the number of young offenders receiving jail sentences has fallen sharply, permitting provinces to close some youth correctional facilities.

At Ottawa's courthouse, the Collaborative Justice Project, which mediates pre-sentence agreements between victims of serious crime and their offenders, has attracted international attention.

- In 1997, the RCMP adopted an extra-judicial restorative justice model, known as community justice forums, to deal with relatively minor offences, mostly committed by youths or young adults.

- For the past three years, one unit at the federal minimum-security prison in Grande Cache, Alberta, has been run entirely on restorative justice principles.

- Sentencing principles added to the Criminal Code in 1996 instruct judges to use jail as a punishment of last resort while encouraging offenders to be accountable for the harm they have caused and make reparations to victims and the community. Conditional sentences, also added to the Code in 1996, are being widely used as an alternative to prison.

- In Nova Scotia, restorative processes for young offenders have been operating province-wide since 2001.

- And increasingly, healing circles and sentencing circles -- traditional native justice practices that echo many restorative ideas -- are being used to deal with crimes committed by aboriginal Canadians.

According to the Justice Department's David Daubney, these influences have helped to reduce Canada's traditionally high adult incarceration rate from about 133 per 100,000 population in the mid-1990s, the fourth-highest among Western democracies, to around 109 today, which places us ninth.

New Zealand is a world leader in implementing restorative justice ideas. Since 1989, most serious youth offenders have been sent to family group conferences, encounters inspired by Maori traditions that bring together victims, offenders, their families and police to devise plans through which offenders can repair harm to victims. New Zealand is now expanding that model to adult offenders, targeting serious crime.

Australia is using similar models to divert young offenders from the courts. The British government has begun public consultations and a major pilot project with the aim of using restorative techniques wherever possible in the criminal justice system.

In continental Europe, countries such as Belgium, France, Austria and Germany are using restorative ideas as an alternative to the courts. Thailand has recently embraced the family group conference approach for juveniles charged with crimes that carry sentences of less than five years. Even the United Sates, where tough-on-crime initiatives have produced the world's highest incarceration rate, has hundreds of community-based restorative justice projects.

In 2002, the economic and social council of the United Nations adopted a Canadian resolution urging countries to consider the use of restorative justice and outlining its fundamental principles. And restorative ideas are at the root of truth and reconciliation commissions, such as the one used to promote social healing in post-apartheid South Africa.

Need more evidence that restorative justice ideas are entering the mainstream? The April 2004 issue of O, the Oprah Magazine, featured a sympathetic article on the concept.

Despite these accomplishments, the future of restorative justice in Canada remains uncertain. While governments have been rhetorically supportive -- federal Justice Minister Irwin Cotler says restorative justice is one of his top priorities -- they have yet to shift meaningful resources from the traditional justice system.

The Fraser Region Community Justice Initiatives Association in Langley, B.C., provides an instructive example. Since 1982, it has run well-regarded restorative justice programs out of its modest offices in a suburban strip mall.

Two years ago, it lost its funding from the B.C. government for the adult component of its Victim Offender Reconciliation Program, known as VORP. After a guilty plea, the courts refer suitable cases to the program, which helps arrange agreements between victims and offenders. This year, the province announced it was withdrawing funding for VORP's youth component as well.

It's not because the programs weren't working. On the contrary, both victim and offender satisfaction was consistently high, and offender compliance with mediated agreements was above 95 per cent. But the B.C. government has been in cost-cutting mode, and restorative justice programs are seen as frills.

"We talk about death-by-pilot-project," says Sandi Bergen, co-director of Community Justice Initiatives. "It happens again and again."

Says Barry Stuart, a former judge in the Yukon who pioneered the use of sentencing circles in Canada: "There are people who have made huge differences in people's lives who struggle from year to year to keep their program together."

Indeed, evaluations of restorative justice programs have repeatedly pointed to their effectiveness. A 2001 analysis by the Canadian Department of Justice that examined 35 restorative justice programs found that victims and offenders who participated in them are more satisfied with their outcomes than those who go through the traditional justice system. Offenders were also substantially more likely to honour restitution agreements than court-imposed orders.

And most studies show small reductions in recidivism rates among offenders who have participated in a restorative process, suggesting they encourage more criminals to change than does imprisonment. In other words, there is evidence that restorative justice helps make communities safer.

Given these findings, why have most governments been hesitant to commit ongoing resources to proven restorative justice programs?

Part of the explanation lies in the justice system's understandable instinct for self-preservation. Restorative justice threatens the system's hegemony over justice, and thus imperils the jobs of current actors, from prison guards to judges. Indeed, unions representing prison guards have already complained about jobs lost because of the shift away from incarceration under the Youth Criminal Justice Act.

Another part of the answer derives from genuine concern over the consequences to the legal system of a widespread embrace of restorative justice. These include fears that it could undermine legal safeguards such as the presumption of innocence and due process principles for accused persons, and erode the idea of proportional sentencing that is fundamental to the criminal justice system.

But restorative justice also demands something that may spook governments even more. It requires a fundamental rethinking of our concept of justice -- a concept that, for most people, still involves what University of Ottawa law professor David Paciocco calls the "human impulse" in favour of punishment. "As unflattering as that is to the state of our humanity," he says, "I think it's a reality that can't be ignored."

Certainly, politicians ignore the public appetite for punishment at their peril. If voters perceive restorative justice as soft on crime because it prefers reconciliation and healing to statutory minimum sentences, it may be a long time before governments back their supportive words with serious dollars.

- - -

Our punitive response to crime is now so ingrained that most people can't conceive of anything else as justice. But our reliance on incarceration as our primary response to crime is actually fairly recent, not reaching full flower until the early 19th century. (The first modern prison, the Walnut Street Jail in Philadelphia, opened in 1790.)

In fact, argues Australian criminologist John Braithwaite, restorative justice -- not punishment -- "has been the dominant model of criminal justice through most of human history for perhaps all the world's peoples."

That's not to suggest that all was sweetness and light in the days of pre-modern justice. As Mr. Braithwaite, a leading restorative justice theorist, points out, most early societies also embraced retributive traditions that often were far more brutal than anything meted out by contemporary criminal justice. For instance, those dispensing private justice had a fondness for castration.

But recourse to punitive solutions normally occurred only after efforts at restitution and reconciliation had failed. In particular, the idea of repayment as a way of redressing wrongdoing has a long history, dating back as far as 2000 B.C. The objective was to prevent violent retaliation against offenders.

In Roman times, what we now define as crime was classified as civil law. "When Roman lawyers had the concept of crime in their mind, they associated it with the need for compensation, indemnification, amends, satisfaction, remuneration or acquittal," writes Dutch criminologist Herman Bianchi in his 1994 book, Justice as Sanctuary: Toward a New System of Crime Control.

"With few exceptions, we find compensation and penitence to be the normal solutions in ancient societies to crime conflicts, whereas revenge or retaliation was a deviance from the norm."

The punitive system of crime control had its origins in Middle Ages Europe. The first "crime" in the modern sense was heresy as defined by the Roman Catholic Church, most often punished by excommunication, though heretics were burned at the stake during the Inquisition. The next was witchcraft, almost invariably a burning offence.

"Only in the early 16th century," writes Mr. Bianchi, "did secular rulers begin, for the first time, to develop an organized interest in the punitive repression of what today we call criminality: crimes of violence and of property."

According to Mr. Bianchi, what heresy had become to the church, crime became to the state as secular authorities adopted the punitive system to bolster their own power. Crime was no longer a conflict between citizens but "a conflict between the state and the accused."

With the rise of state justice came brutal punishments, including torture and death, often administered in public as a visible expression of state power. In part, says Howard Zehr in his seminal 1990 book about restorative justice, Changing Lenses, the development of prisons was a reaction to these excesses -- a more humane, calibrated and scientific way of administering pain, beyond the sight of a public growing increasingly squeamish about public displays of suffering.

American Quakers were early champions of prisons, believing them to be a means of encouraging repentance and conversion. Later, prisons were seen as laboratories for changing behaviours and personalities, a largely vain hope that persists to this day.

The state monopoly over doling out justice has had profound consequences -- some good, some bad.

Because the consequences of a guilty finding can be so dire, Canada now has unprecedented protections for people accused of crimes, and an apparatus for determining guilt or innocence that is one of the best the world has known.

But we also have victims who feel ignored and even abused by the faceless system. We have offenders who are instructed by their lawyers to deny responsibility for their crimes and suppress all public expressions of remorse. We have communities that have "lost the capacity to handle conflict," in the words of Liz Elliott, co-director of Simon Fraser University's Centre for Restorative Justice.

We also have citizens who believe that crime-control policies, such as incarceration, can actually reduce crime. But such politics don't have much impact on crime rates, says the University of Ottawa's Julian Roberts. "It's a depressing kind of conclusion, but I think it's a pretty accurate one. The public hasn't really got that message."

And we have prisons that do more to reinforce criminal behaviour than to discourage it, a fact confirmed by persistently high recidivism rates. Even those who somehow resist the "con culture" often reoffend because the stigma attached to being an ex-convict makes them virtually unemployable. As Herman Bianchi has pointed out, "in a very real sense, every prison sentence is a life term."

Yet governments have responded to the justice system's failures by hiring more police officers, more crown attorneys and judges, and building even more courthouses and prisons, in large part because that's what the public demands. According to Statistics Canada, spending on policing, courts, prosecutions, legal aid and correctional facilities topped $11 billion in 2000-2001.

"We're the only game around the table in the bureaucracy that can say we want more money next year because we did so badly the year before," says Barry Stuart, the former Yukon judge. "We get more money for failing. So the incentives that are built into the system are not, in fact, to do effective work."

According to Judge Stuart, the public has come to accept the justice system's failings as a necessary evil. "They don't have a vision of an alternative way of dealing with crime. So we keep pouring in more and more resources, thinking that if we only had more resources, we'd get ahead of this problem. Which is exactly the wrong way to go."

Is an alternate vision of justice is needed? If so, restorative justice offers precisely that. Its reincarnation of communitarian justice, tapping into ancient traditions and lost wisdoms, may be the agent that challenges our unrequited affair with punishment. It may even help to reshape the lives and values of seven B.C. men with murder on their resume.

- - -

The Series

Today: What is restorative justice? Its origins and aims.

Day Two: Ottawa's Collaborative Justice Project. Restorative justice for serious crime in tomorrow's Citizen's Weekly.

Day Three: Restorative justice and the young. An Edmonton project takes on juvenile offenders.

Day Four: Aboriginal sentencing circles. The roots of reconciliation.

Day Five: Healing the victims. How victim-offender mediation in prisons can deal with crime's after-effects.

Day Six: Breaking the prison code. One Alberta penitentiary tries to change inmates' values.

Day Seven: The case against restorative justice.

Day Eight: What the future holds.