Oct. 6, 2004

TRACEY TYLER |

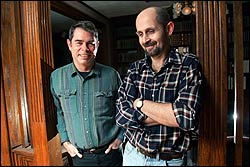

| MARIANNE HELM FOR THE TORONTO STAR |

| As the Supreme Court of Canada begins a hearing today into a move by Ottawa to legalize same-sex marriage, Chris Vogel, left, and partner Richard North reflect on their 30-year union from their Winnipeg home. They were married in the Unitarian Church in 1974. |

Same-sex

marriage may be a new issue for the Supreme Court of Canada, but it's 30 years

of ancient history for Chris Vogel and Richard North.

Vogel, 57, and North, 52, were the first gay couple in Canada to attempt a legal marriage. They failed in the courts in those days before the Charter of Rights and Freedoms but were married by a Unitarian minister in Winnipeg in 1974.

Thirty wedding anniversaries later, Vogel will cast an eye toward the country's highest court today, when a hearing gets under way into the constitutionality of a federal government draft bill that would legalize same-sex marriage.

But the event will have little meaning for him, Vogel said.

"The Supreme Court will certainly say to politicians we must be treated equal in every respect," he said in an interview.

"It will have some utility," he added. "The conservative opponents will put forward their arguments, which are all ridiculous and unfounded, and that will give the court an opportunity to say, not for the first time, these are all ridiculous and unfounded."

Apart from that, Vogel sees the hearing as a "purely academic" exercise.

But some intervenors in the case are still hoping it isn't a constitutionally done deal, and see the hearing as their last chance to preserve the original definition of marriage in the Marriage Act as an exclusively heterosexual institution.

A group called the Interfaith Coalition on Marriage and the Family plans to argue that the equality rights of members of many religious faiths will be violated by allowing same-sex couples to marry.

"There is a concern that the proposed act, out of a desire to achieve equality for some, will seriously exacerbate inequality for other vulnerable groups in society, whose concept of marriage cannot be reconciled with the proposed act and who will be further marginalized from wider civil society," the group says in a written argument filed with the court.

Vogel said he and North attempted to marry because "we believed if people would look at us realistically, our problems would end."

Back then, "few people could say `homosexual' without choking" and "we were spoken of as if we were evil," he said. At the time, gay and lesbian marriages were being performed by clergy in some parts of the United States, notably Arizona, Vogel said.

But when he and North took Manitoba's registrar of marriages to court seeking the right to have their marriage legally recognized, the judge relied on a dictionary definition of marriage to rule against them, he said, adding they also received a legal opinion that an appeal "was hopeless."

In February 1974, they were married in the Unitarian Church, which "in those days did a huge business marrying those that others wouldn't touch," including divorcees, Vogel said.

His parents lived in Ontario and didn't attend the ceremony. But North's parents and sisters were there. Their families were supportive, though initially uncomfortable.

The CBC broadcast portions of the ceremony. "That alerted other relatives, who sent us pillowcases and such," he recalled.

After their pioneering bid to have their marriage legally recognized, Vogel, who is now retired after years with Manitoba's natural resources department, and North, a cabinetmaker and nurse, turned their attention to other struggles.

Their lobbying to reform the federal Immigration Act paid off when the government abolished a section that prohibited the entry of visitors or prospective immigrants who were homosexual or living off the avails of homosexuality.