June 9, 2005

|

|||

|

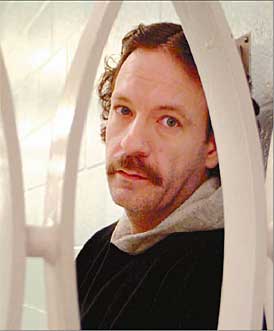

George Pitt never screamed his innocence, never said he deserved anything other than a fair trial. Again and again, the convicted child murderer has tried to kill himself in a New Brunswick prison because, he says, nobody bothered to take seriously his claims of wrongful conviction.

Nobody could believe that the Saint John police were still quietly investigating the 1993 rape and killing of his girlfriend's six-year-old daughter months after Mr. Pitt was condemned to life in prison for the crime.

Last summer the Citizen publicized a secret Correctional Service Canada report, saying not only that police had been investiating the case months after Mr. Pitt's conviction, but that the police chief actually suspected someone else of the murder.

Yesterday, the New Brunswick government re-opened the case, finally deciding to examine exhibits seized from the crime scene that somehow have gone untested until now.

The case was introduced to Jerome Kennedy, a lawyer with the Association in Defence of the Wrongfully Convicted, known for freeing Guy Paul Morin, Donald Marshall and David Milgaard, last year after the Citizen investigated the case.

The Citizen investigation, which appeared last July 31 under the headline "Presumed Guilty," found that the Saint John police had seized seemingly key evidence from the crime scene, including four strands of hair on the girl's body, her nightie, and what appeared to be a bloodstain on a neighbour's apartment door, but for some reason didn't send it to the crime lab for analysis.

The New Brunswick government announced yesterday that it will request that courts release the evidence to be tested.

"It was a potential wrongful conviction," said Mr. Kennedy. " A lot of the systemic issues are present. Therefore, I have reason to doubt the validity of the conviction. However, the DNA testing may prove who the killer is.

"My introduction to this case began with the Ottawa Citizen's story, and a year later, with all the work that we've done, it's amazing to me that there are still so many gaps in the case," he said.

"It's the pursuit of the truth we're all interested in. Give George Pitt a chance to demonstrate his innocence," said Mr. Kennedy, who expressed cautious optimism.

The New Brunswick government agreed yesterday to start testing the first round of exhibits seized from the 1993 crime scene.

The Saint John Police Department never bothered to test the exhibits they seized from the scene, including a used condom.

But prosecutors still won a conviction in the highly circumstantial case that put Mr. Pitt's lifestyle on trial, rather than the evidence. The prosecution never gave the jury a motive.

Mr. Kennedy expressed surprise yesterday at the government's announcement and said it indicated a "new level of co-operation' for re-examining potential wrongful convictions in Canada.

Mr. Pitt, now 40, was convicted in 1994 for the rape and killing of young Samantha Toole, found dead behind her home at the edge of the Saint John River on Oct. 2, 1993. The police might have found her before she had been raped, beaten, choked, and then dumped at the river's edge to drown, but the two officers first dispatched didn't take seriously the missing-child report called in by Samantha's mother.

In fact, according to 911 transcripts obtained by the Citizen, the police officers laughed about it and went about their business.

Gloria Toole, the mother of the dead girl, had to call police four times over two hours and 35 minutes before they finally responded and issued a citywide missing-child alert.

Ms. Toole told police she couldn't find her little girl, gave her address and then explained that she had left the child with a sitter the night before and that when she woke up, Samantha wasn't around. The girl's mother had skipped line-dancing at her church for a night of drinking, and then slept in until noon.

The police dispatcher never asked her for a description of the missing girl and said a cruiser, Car 109, was on its way. Behind the scenes, on the police radio, officers were having a good laugh. "Huh, I bet she had no babysitter, no doubt," replied Const. Tom Clayton, the responding officer.

The dispatcher later told the officer that Ms. Toole in fact had a sitter, and repeated there was a little girl missing.

The constable laughed, and the dispatcher weighed in with: "Just f--king typical."

"Really, eh? Unreal, isn't it?" Const. Clayton agreed.

Then Ms. Toole telephoned again: "I'm wondering when the police were going to show up."

This time, another officer on the desk took the call, and assured her that a cruiser had been dispatched almost an hour earlier, and said he had double-checked, and Saint John police would be there shortly.

The dispatcher called Car 109 and inquired why it hadn't addressed Ms. Toole's call. The constable had decided instead to investigate a shoplifting report.

Three hours after the police finally took the call seriously, a neighbour found Samantha Dawn Toole, with brown, shoulder-length hair and blue eyes, and a loose bottom front tooth. She had been in Grade 1.

Her body, somewhat stiff, lay face-up, with arms at a 90-degree angle, fists clenched. Inside them, seaweed.

Her fingers, lips and earlobes were blue and her body was wet and cold.

Her face was bruised and scraped. She was wearing a dirty nightie and soaked, muddy socks. Her left wrist had been fractured. Investigators later noted massive trauma to her vagina and rectum. She had been choked, and then she had drowned.

The case against Mr. Pitt, who had planned to adopt the girl, was a circumstantial one; police saw Mr. Pitt as a prime suspect almost immediately.

The girl's mother told police she found Mr. Pitt doing a load of laundry at 4 a.m., when she arrived home after a long night of drinking.

The police crime lab unearthed one square centimetre of the girl's blood on a bedspread, which had been part of the load of laundry police were told Mr. Pitt had been seen washing. There was also a larger bloodstain on a comforter, but police were unable to identify its origin.

The Citizen also obtained a series of statements the dead girl's mother gave police. She made them over a period of a week, and they were never heard at trial.

After first saying she knew nothing about the killing, she implicated Mr. Pitt, saying she witnessed the murder. But her story didn't fit the evidence at the scene and she later admitted that she could have simply imagined it.

She told the Citizen last year that she regrets leading the police astray.

The trial heard much conflicting testimony, and a family friend lied when asked his whereabouts on the eve of the killing.

The jury never heard from the accused, who said he didn't take the stand because he thought the case against him was too weak to convict him.

He's always maintained his innocence.

Mr. Pitt has been in and out of prison since he was 11. He's an alcoholic, and his steadiest pay has always been welfare.

To believe Mr. Pitt's story, that he didn't kill the girl, you'd have to first see nothing wrong, or unusual, about doing laundry at 4 a.m., and then dismiss the prosecution's inference that he took flight out of guilt once the police were called.

He's always said that he's only guilty of hanging out with the wrong crowd.

Guilty or innocent, the only thing certain about George Pitt's story is that it's a lousy one. Three sisters. Two brothers, one also a convict. His father, Ron Pitt, beat them hard and drank even harder.

Young George was just seven when his family home burned to the ground. His mother put him in the care of the government, but instead of landing in a foster home, he ended up in an orphanage, where he was beaten and molested.

He later moved back home with his mother, and he stopped going to school when he turned 11.

The Saint John police charged him with truancy and the court placed him on probation, but he was charged again for skipping class.

The police picked him up and he was sentenced to three months in a youth jail outside Fredericton, an hour from home.

Young George was raped at least 15 times by Karl Toft, one of the guards. When he got out, he started drinking to forget, then turned to drugs, then overdoses, then suicide attempts.

Source

Ottawa Men's Centre

www.OttawaMenscentre.com 613-797-3237 (797-DADS)