Daddy, what did you do in the men's movement?

Robert Bly may have retreated to his sweat lodge, but the reconsideration

of masculinity and fatherhood he helped initiate hasn't ended.

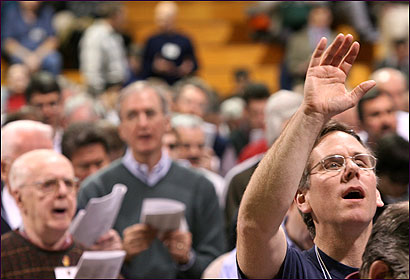

GOD AND MAN: At the first annual Catholic

Men's Conference, held in Boston in March, the 2,200 attendees were

urged to be "the spiritual leaders" of their homes. (Globe

Staff Photo / Wendy Maeda) |

By Paul Zakrzewski | June

19, 2005

THE LAST TIME most of us heard a joke about grown men getting in touch

with themselves by beating on drums or hunkering down in sweat lodges, the

first Gulf War was in full swing, and Nirvana ruled the airwaves. But for a

brief moment in the early 1990s, the ''men's movement" was everywhere

you looked, from Jay Leno to ABC's ''20/20" to the pages of Esquire and

Playboy.

And if the movement was never particularly large or diverse - according to

Newsweek, about 100,000 mostly white, middle-aged men had attended a patchwork

of weekend retreats, conferences, and workshops by 1991, when the movement

peaked - it struck a chord with a country that appeared confused about

contemporary manhood. Books by Sam Keen, Michael Meade, and other leading

figures in the movement sold hundreds of thousands of copies, while Robert Bly's

''Iron John," a cultural exegesis on wounded masculinity in the form of an

obscure fairy tale, spent more than 60 weeks on the New York Times bestseller

list.

Arguably, the Bly-style mythopoetic men's movement, as it was known, can be

traced back to the late 1970s, to men's consciousness-raising groups and

masculinity classes in places like Cambridge, Berkeley, and Ann

Arbor

. However, it was Bly's collaboration with Bill Moyers on the 1990 PBS

documentary ''A Gathering of Men" that turned the groundswell of retreats

and gatherings into a national phenomenon.

With his lilting Minnesota brogue and occasional impish aside, the

grandfatherly Bly talked about the Wild Man, avatar of a kind of inner masculine

authenticity lost during the Industrial Revolution, when fathers left the

homestead (and their sons) behind and went to work in factories. With the lore

and lessons of manhood no longer passed on to younger generations, men lost a

certain kind of male identity, even the sense of life as a quest. ''Many of

these men are not happy," Bly wrote of today's ''soft males," as he

called them. ''You quickly notice the lack of energy in them. They are

life-preserving, but not exactly life-giving."

Today, however, the drums have largely fallen silent. While there are still

weekend retreats - for example, the ManKind Project, which boasts more than

two-dozen centers worldwide, conducts ''New Warrior Training Adventures"

for some 3,000 men every year - these are mostly affairs for the already

initiated.

''The men's movement as we knew it has gone underground," says Ken

Byers, a San Francisco-based writer and therapist who attended dozens of

retreats in the early 1990s. ''Unless you're involved in that underground,

there's very little way for the average American man to connect with it."

Of course, Bly's mythopoetic movement was only one of several, often

contradictory men's movements. Since the 1970s, ''men's rights" advocates

have pushed for fathers' parental rights, while profeminist groups such as the

National Organization of Men Against Sexism and the national network of Men's

Resource Centers want men to become more accountable for sexism, homophobia, and

violence. And in the wake of Bly, new mass men's movements seized the media

spotlight. In 1995, Nation of Islam leader Louis Farrakhan organized the Million

Man March, to inspire African-American men to rebuild their lives and

neighborhoods. Meanwhile, by the mid-1990s, the Christian evangelical Promise

Keepers were packing hundreds of thousands of men into football stadiums each

year for rallies that, like the ''muscular Christianity" movement a century

before, encouraged them to reclaim their masculinity by retaking control of

their families with the help of Jesus Christ.

Page 2 of 3 --

So what happened to Bly's mythopoetic movement? The negative media coverage,

such as Esquire's ''Wild Men and Wimps" spoof issue in 1992, didn't exactly

help. But there were other factors, too. For one thing, even many of the men not

inclined to dismiss Bly-style gatherings as silly found themselves mystified by

the rarefied Jungian concepts tossed around the campfires like so many

marshmallows. ''Many of the men I saw worked really hard at trying to figure out

the mythology, but they just weren't getting it in the belly," says Byers,

echoing the title of Sam Keen's bestselling book.

Part of the problem, too, was the mythopoetic movement's complex relationship

to feminism. On the one hand, some feminists construed Bly's attack on feminized

males as reactionary. ''I'd hoped by now that men were strong enough to accept

their vulnerability and to be authentic without aping Neanderthal cavemen,"

Betty Friedan told The

Washington Post

back in 1991. (Bly denied that there was anything anti-woman about his ideas.)

What's more, the movement itself could never get beyond the fact that unlike the

feminist movement - which itself had lost steam by the 1990s, as women achieved

more economic and financial power - Bly and his followers never had any clear

political agenda to drive them forward.

Then again, perhaps the death of the men's movement has been greatly

exaggerated. Like the women's movement, it may just be that its biggest lessons

have simply been absorbed into the culture, minus the pagan fairy tales and faux

Native American rites. For example, it's evident to any man who carves out time

in his busy week to meet his buddies for a drink that, as Bly suggested, men

benefit from time spent in ''ritual space" - that is, with other men. (Full

disclosure: For the last year I've met with other men in their 30s and 40s for a

weekly discussion group in Jamaica Plain, where we talk about everything from

career issues to complicated relationships with our fathers.)

And whether or not they can tell their Wild Man from their King (another

figure in Bly s complex mythological scheme), many younger men want to be more

engaged in family life than their own fathers were. In 1992, about 68 percent of

college-educated men said they wanted to move into jobs with more

responsibility, according to a recent study by the Families and Work Institute.

A decade later, the number fell to 52 percent. Meanwhile, a 2000 study by the

Radcliffe Public Policy Center found that the job characteristic most often

ranked as very important by men ages 21 to 39 was a work schedule that allowed

them to spend more time with their families. Seventy percent said they were

willing to sacrifice pay and lose promotions to do so.

Page 3 of 3 --

Still, the reality of being a good father often poses more of a challenge for

these young men than they expect, often in ways that Bly himself might have

explained. ''One of the central problems is that the image that men have of

immersing themselves in families is a very maternal one," says Mark

O'Connell, a Boston-based psychologist and the author of the recent book ''The

Good Father: On Men, Masculinity, and Life in the Family" (Scribner).

''They are trying to follow something that isn't altogether authentic and

reflective of the different strengths that men bring to the table."

America, of course, is a different place than it was when Bly wrote his best

seller. Today, when men get together in organized men's groups, they are more

likely to talk about Jesus Christ than Iron John.

Nevertheless, there's more than a touch of Bly in John Eldredge's ''Wild at

Heart: Discovering the Secret of a Man's Soul," an evangelical call-to-arms

that has sold 1.5 million copies since it was published in 2001 and that has

helped launch a series of weekend workshops. Men still go into the woods, but

instead of wrestling with the Wild Man, they meet Jesus, described as a kind of

fierce, unfettered energy that transforms ''really nice guys" (a version of

Bly's ''soft males") into passionate beings ready to tackle life's

adventures, including romantic relationships. ''Not every woman wants a battle

to fight, but every woman wants to be fought for," Eldredge

observes in a passage that might have been written before Betty Friedan was

born.

Meanwhile, after years of dwindling attendance due to financial problems, the

Promise Keepers are staging a comeback this summer, hoping to fill 20 stadium

rallies across the country. And in March, the first annual Catholic Men's

Conference, inspired by the Promise Keepers, attracted 2,200 men to Boston, who

came to listen to speakers ranging from Archbishop Sean P. O'Malley to ''Passion

of the Christ" star Jim Caviezel to Bush administration official James

Towey. (According to organizer Scot Landry, the event's success was fueled by

the growing number of men's fellowship groups in the Boston Archdiocese, which

have spread from a handful of parishes 5 years ago to between 30 and 50 today.)

The emphasis was on the importance of traditional Catholic teachings on

sexuality and the family, under which men - not their wives - are called to be

''the spiritual leaders of your home," as one speaker put it.

Even if we're not likely to see maverick poets and Jungian therapists on

television specials and magazine covers again any time soon, one thing is clear.

The Bly-style men's movement highlighted a powerful urge for men to commune with

each other that persists today, even among those who wouldn't be caught dead

within miles of a drumming circle.

''There was something about Bly's language and approach that was easy to

caricature," says O'Connell. ''But he was on to something really important,

and a lot of what he was talking about got lost in translation."

Paul Zakrzewski is the editor of ''Lost Tribe: Jewish Fiction from the

Edge" (Harper Perennial). He lives in Jamaica Plain. E-mail pzak@verizon.net.

© Copyright 2005 Globe Newspaper Company.

Source

www.OttawaMensCentre.com

613-797-3237

613-797-DADS