Two possible distant relatives,

including Rich, volunteered to provide DNA samples if it

would help identify the baby, but they were too far

removed for their DNA to determine parentage, said

Cairns.

"The answer is, we'll never know," said

Cairns.

Rich is sure she knows whose baby it

wasn't. And she has a theory about who the mother may

have been.

Her aunt and uncle, Della and Wesley

Russell, a postal clerk, owned the house on Kintyre. But

Rich is sure Della could not have been the mother.

For one thing, Della was certain she

could never become pregnant. If she had by some miracle

become pregnant, she would have had no reason to hide

the baby, says Rich.

Besides, Rich adds, except for a few

weeks in summer when she went to visit relatives in the

U.S., Rich was always with Della.

It would have been impossible for Della

to carry a baby to term without Rich noticing.

The boarder, George Turner, worked at

the telegraph office. He lived in the house for nearly

10 years until he married.

He was a perfect gentleman, and if he

had gotten a girl pregnant, would have married her, says

Rich.

Her father Charles never dated anyone

after his wife died.

He was so devoted to her that every year

on Rich's birthday, he would open a trunk he kept,

filled with her mother's things, and present her with a

gift that he said was from her.

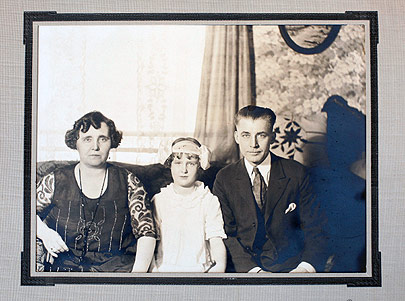

Rich thinks it's possible the baby may

have belonged to Della's much younger sister, Alla Mae,

a beautiful, blue-eyed blonde, who would have been in

her early 30s in 1925.

Mae's first, early marriage had ended in

divorce.

She lived in New York City, but often

visited her Toronto relatives.

Rich thought Mae was glamorous. She wore

black satin and dated bandleaders. She carried around a

toy poodle she called "Teddy." She could strike up a

conversation with anyone.

Rich remembers on one visit Della

admonishing Mae for moving furniture because she was

pregnant.

"I don't know how authentic that is,"

says Rich. "I would like to think it was so, then I

would know she was the mother, but I don't know, it was

so vague."

Life seemed happy in the Russell

household.

Della and Wesley were loving, friendly

people, good neighbours, although they weren't overly

sociable.

Wesley liked home brew, but Rich never

remembers seeing him drunk.

Everything changed when Rich was a

teenager and Della learned that her husband of 30 years

was having an affair with a younger woman.

Della suffered a mental breakdown and

Wesley had her committed to a mental institution. His

lover moved into the house, and Rich no longer felt

comfortable living there.

When the American boy she'd been dating

announced he'd found a job as an assistant manager at a

Loblaw's, she married him in Medina.

They were married for more than 60

years.

Rich's father also left the house. Rich

heard that the woman Wesley had the affair with turned

it into a boarding house after he died in 1939.

Della outlived her husband and his

lover, but never left the mental institution.

Her brother Charles visited her every

day.

Rich went three times but said Della

never spoke to her.

Rich and her husband made their lives in

Medina, running a florist shop.

They raised one boy and had two

grandchildren and six great-grandchildren.

Her husband died 10 years ago. Rich

still lives on her own.

Baby Kintyre, as he has come to be

known, will be honoured at a ceremony organized by the

Canadian Centre for Abuse Awareness on Friday, October,

12, and buried at Elgin Mills Cemetery.

"If I'm able to go, I feel that if that

baby is related to me, I certainly owe it to him," said

Rich.

"I just keep wondering if he's a part of

me."