Sudden Divorce Syndrome

December 19, 2007

Like every husband who suddenly turns into an ex, Martin Paul, a pleasant,

unassuming 51-year-old, knows exactly where he was when it happened. He was

sitting on the back porch of his pricey hilltop house in the Boston suburbs one

sunny Saturday morning, relaxing over coffee.

Paul is a professional collector, primarily of coins, but of other rare objects

as well: Sonny Liston’s ring belt; a submarine that appeared in the James Bond

film The Spy Who Loved Me. It wasn’t

easy to build up his collecting business, but he had finally got it humming, and

he was pulling down close to seven figures a year. Plus, the oldest of his three

sons had suffered a frightening brain injury, but after two years of treatment,

he had finally recovered enough to go to college. For the first time in a very

long while, life was good.

And so, that Saturday, he wanted to tell his wife he was thinking about finally

easing off a little. They’d started going on expensive vacations in Europe and

Hawaii, and he figured she’d be pleased at the prospect of taking more trips

together, or at least at the prospect of seeing him around the house a little

more, and not buried in his basement office. He had met her in graduate school

over a quarter century ago, and they’d had their ups and downs, but he was still

crazy about her. And he thought that, with a little more time together, she’d be

crazy about him again too.

But no. She scarcely listened to any talk of retirement, or of vacations, or of

anything he had to say. She had plans of her own.

“I want a divorce,” she said.

Paul was so stunned that he thought he must have misheard her. But her face told

him otherwise. “She looked like the enemy,” he says. He started to think about

everything he’d built: the thriving business, the wonderful family, the nice

life in the suburbs. And he thought of her, and how much he still loved her. And

then, right in front of her, he started to cry.

That night, he found a bottle of whiskey, and he didn’t stop drinking it until

he nearly passed out.

Things turned shitty very fast. His wife took out a temporary restraining

order, accusing him of attempting to kidnap their youngest son. The claim was

never proved in court. Then, with the aid of some high-priced lawyers, she

extracted from him a whopping $50,000 a month—a full 75 percent of his monthly

income. Barred from the house, he was not allowed regular access to the office

he used to generate that income. (On the few times he was permitted inside, his

wife did not let him use the bathroom. She insisted that he go outside in the

woods.) “My lawyer kept telling her lawyers, ‘You’re killing the Golden

Goose,’ ” recalls Paul. “But they didn’t care.”

Crushed by the payments, and unable to work, he soon faced such a severe

cash-flow crisis that he had to declare bankruptcy. His wife still did not

relent. She charged that Paul had been abusive toward one of their sons. Paul

says the charge is absurd, but it did its work, limiting his visitation rights.

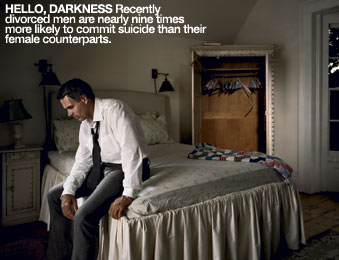

Paul was sleepless and nerve wracked; his spirits plunged. He still missed his

old life with his family. He missed the sound of it—the bustle of all the

activity, the life. “I can’t stand the silence,” he says. “I miss hearing my

wife breathe as she lay in bed beside me.” In his desperation, he twice

overdosed on prescription medication, but managed to call 911 each time before

the drugs took full effect, and medics rushed him to the hospital in time. “I

don’t want to die,” he says wearily. “I want to live. But I can’t live with this

torture.” He did manage to keep a few mementos of his former life. Pictures,

mostly. But also the kids’ baby shoes. “I was always the emotional one,” he

says. “But that’s all I have—the shoes, a few pictures. That’s all. I used to be

jovial, happy. But not now. I’m a broken man.”

Sudden Divorce Syndrome. You won’t find it in the

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental

Disorders, that bible of psychiatric illnesses, but you will find it in

life. In a 2004 poll by the AARP, one in four men who were divorced in the

previous year said they “never saw it coming.” (Only 14 percent of divorced

women said they experienced the same unexpected broadside.) And few events in a

man’s life can be as devastating to his physical, mental, and financial health.

“I meet men all the time who are going through breakups, and it’s very common

for them to say it caught them by surprise,” says Los Angeles–based sex

therapist Lori Buckley, PsyD, host of “On the Minds of Men,” a weekly

relationship podcast on iTunes. The warning signs are usually there, claims

Buckley, but the male mind is simply not very adept at recognizing them. “When

women make up their mind that the relationship is over, they stop talking about

the relationship,” she says. “Men interpret a woman’s lack of complaining as

satisfaction. But more often, it’s because she’s simply given up.”

To understand how common this scenario is, consider figures provided by John

Guidubaldi, a former member of the U.S. Commission on Child and Family Welfare.

Nationwide, Guidubaldi reports, wives are the ones to file for divorce

66 percent of the time, and, in some years, that figure has soared to nearly 75

percent. “It is easier to end a marriage than it is to fire an employee,” says

Guidubaldi. If she wants out, it’s over. “You can get a dissolution of marriage

on the basis of nothing.”

Oftentimes, men have a divorce sprung on them in midlife, when their kids are

more self-sufficient and they’ve finally started to think they were over the

hump. Like Martin Paul, they could start to relax. But that’s exactly the time

of life when the instance of divorce begins to swell (another occurs shortly

after marriage). Joe Cordell, of the law firm Cordell and Cordell, which

specializes in representing men in domestic cases, attributes this to wives

deciding as they approach age 40 that it’s now or never for getting back into

the marriage market. It’s the same phenomenon as rich guys trading in their

long-time partners for trophy wives. Only it’s the women who are shedding men.

It didn’t used to be this way. While divorce has been legal for nearly two

centuries, it was long a topic of such mortification that it was considered a

last, desperate resort. The 1960s changed all that. The free-love decade both

increased the inclination to divorce and dropped the social resistance to it.

The rising financial independence of women began to free them from a need to

stay in a stultifying or abusive marriage. As a result, divorce soared, doubling

by most measures. But the stereotypical divorce story—man marries, starts a

family, meets a younger women, and leaves his wife—just isn’t as common as we

are led to believe.

“Marriage changes men more pervasively and more profoundly than it changes

women,” explains sociologist Steven Nock, author of Marriage in Men’s Lives.

“The best way to put it is, marriage is for men what motherhood is for women.”

Marriage makes men grow up. Nock observes that many men before marriage are

indifferent workers, and, after hours, are likely to be found in bars or zoned

out in front of a TV. After marriage, they are solid wage earners, frequent

churchgoers, maybe members of a neighborhood protection association. But divorce

takes that underpinning away, leaving men strangely infantilized and unsure of

their place in the world. They feel like interlopers in the stands at their

children’s soccer games or in the auditorium for their school plays.

Compounding this pain, men find the deck is stacked against them. The divorce

system tends to award wives custody of the children, substantial child support,

the marital home, half the couple’s assets, and, often, heavy alimony payments.

This may come as startling news to a public that has been led to believe that

women are the ones who suffer financially postdivorce, not men. But the data

show otherwise, according to an exhaustive study of the subject by Sanford L.

Braver, a professor of psychology at Arizona State University and author of

Divorced Dads: Shattering the Myths.

“The man is in a lot poorer condition than the popular media portray,” he says.

“This idea of the swinging, happy-go-lucky, no-worries single guy in a

bar…that’s just not it at all.” The misconception was fueled by Harvard

professor Lenore Weitzman’s widely cited book,

The Divorce Revolution: The Unexpected Social and Economic Consequences for

Women and Children in America.

Weitzman’s 1985 tome claimed that postdivorce women and children suffer on

average a 73 percent drop in their standard of living, while the divorced men’s

standard of living increased by 42 percent. Years later, Weitzman acknowledged a

math error; the actual difference was 27 percent and 10 percent, respectively.

But Braver says even that figure is based on severely flawed calculations.

Weitzman and other social scientists ignored men’s expenses—the tab for

replacing everything from the bed to the TV to the house—as well as the routine

costs of helping to raise the children, beyond child support. Even the tax code

favors women: Not only is child support not tax deductible for fathers, but a

custodial mother can take a $1,000 per child tax credit; the father cannot, even

if he’s paying. As “head of the household,” the mother gets a lower tax rate and

can claim the children as exemptions. If the ex-wife remarries, she is still

entitled to child support, even if she marries a billionaire. Indeed, every year

men are actually thrown in jail for failing to meet their child-support

obligations. In the state of Michigan alone, nearly 3,000 men were locked up for

that offense in 2005.

But for many men, the real pain isn’t financial, it’s emotional: “Men depend on

women for their social support and connections,” says Buckley. “When marriages

end, men can find themselves far more alone than they ever expected.” In a

large-scale Canadian survey, 19 percent of men reported a significant drop in

social support postdivorce. Women are customarily the keepers of the social

calendars, and all that is implied by that, providing for what University of

Texas sociologist Norval D. Glenn calls the “intangibles” that can create much

of a man’s sense of place in the world. More often than not, wives send out the

Christmas cards; they stitched that cute Halloween costume their daughter wore

in second grade; they recall the names of the neighbors who used to live two

houses down. The men who bear all these unexpected burdens do so alone, in a

strange place, while their ex-wives and children live in the houses that used to

be theirs. For an ex-husband to enter that house can feel like trespassing, even

though it was paid for with his own money, or sometimes, built with his own

hands.

Long before his wife came along, a frame-store owner named Jordan Appel, 55, had

built a fine house for himself atop West Newton Hill in one of the fancier

Boston suburbs. He loved bringing in a wife and then adding two children. “It

felt so wonderful to say ‘my wife’ and ‘my children’ and feel part of a

community.” He volunteered for the preschool’s yard sale; his wife took up with

a lover. Sometimes she slept with him in Appel’s own house; in time, she decided

to divorce Appel. As these things go, he was obliged to leave the house, and, as

it happened, the community too. Money was so tight that he ended up sleeping in

a storage room above his frame shop two towns away. His ex-wife works part-time

on the strength of Appel’s child custody and alimony payments, and spends time

with her boyfriend in Appel’s former house. She lives rather well, and he has to

make $100,000 a year to support her and the children, which amounts to 70-hour

workweeks. One day, he went back to his house and discovered many of his

belongings out on the sidewalk with the trash. “My body feels like it’s

dissolving in anger,” he says. “I’m in an absolute rage every single day.”

“What are five of the biggest stressors a human being can face?” asks Ned

Holstein, MD, executive director of Fathers and Families, a Massachusetts-based

reform group for divorced dads. “One: the death of a child. Two: the loss of a

spouse. Three: the loss of a home. Four: a serious financial reversal. And five:

losing a relationship with a child. All of these except the first are combined

in a father’s experience of divorce. People always think the man is a lone wolf

and he can take care of himself. Well, he’s also a human being, and people don’t

think through what that means for men.”