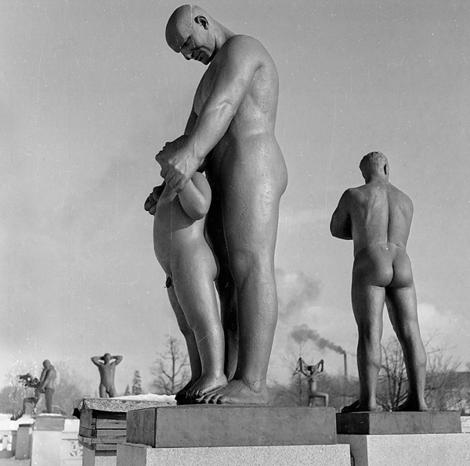

Devolution of man … it has been found sperm abnormalities can be passed from

parents to their children.

Photo: Getty Images/Haywood Magee

Devolution of man … it has been found sperm abnormalities can be passed from

parents to their children.

Photo: Getty Images/Haywood Magee

Australian and overseas biologists have long argued the male testis, DNA and sperm are under attack from environmental contaminants, and the end game could be the male sex-defining Y chromosome's destruction.

Counsellors trying to help couples conceive have been desperate to give would-be fathers more precise advice on chemicals to avoid and lifestyles to lead - but are now learning that in some cases the damage to men's fertility may have happened way back in their mother's womb.

The discovery has been made in the new science known as "epigenetics", which strongly suggests chemical damage is causing abnormal sperm and male infertility via a pregnant woman's exposure to contaminants, passing infertility not only to her son but successive sons - overturning old assumptions about biology and DNA.

Until recently, it had been assumed a gene had to be mutated for a disease to be inherited. But studies on pregnant rats exposed to pesticides show male offspring can inherit reproductive disorders, and pass them on to their children and grandchildren, through an abnormality that affects the activity of genes but leaves the sequence of the DNA code unchanged.

Long-held fears of declining sperm numbers in Western countries are just one part of the problem for men's reproductive prospects. In 1992, a meta-analysis, published in the British Medical Journal, of the world literature reported that between 1938 and 1990 there was a halving of sperm concentration in human semen. A review by researchers in the United States in Environmental Health Perspectives in 1997 reanalysing the data over the same period suggested a 3 per cent per year decline in Australia and Europe - twice that of US - on limited Australian data.

But the claims of falling sperm were dismissed as "extravagant" by a Sydney researcher, Professor David Handelsman of the ANZAC Institute. In a 2001 paper published in the journal Reproduction, Fertility And Development he criticised the way disparate studies had been aggregated, and the US researchers toned down earlier estimates. Yet Handelsman conceded some cancer registry data indicated a gradual rise in testicular cancer, which he could not explain.

5990 men aged 40 and over found almost 8 per cent had tried and been unable to have children. This was "the first real estimate of infertility prevalence in Australia", the authors suggested, but it was unclear which partner was infertile, and no historical Australian comparison exists. Thirty-four per cent of the 40-plus men who had no children still wanted to be fathers.

Among Western couples, roughly one in seven seek treatment for infertility, at least half due to a male problem, and one in 35 babies is now born with assisted conception.

In Australia and New Zealand in 2005, there were 21,420 assisted reproduction technology cycles in which an oocyte or embryo was transferred which involved ICSI - intracytoplasmic sperm injection. This involves a single sperm being injected into an egg for fertilisation outside the body and replaced in the uterus, usually because the male has a low sperm count, it is abnormal or has poor motility. In recent years, ICSI has outnumbered in-vitro fertilisation involving an oocyte or embryo transfer. In 2005, it outnumbered by nearly 4500 IVF transfer cycles.

The adverse influence of "xenobiotics" - molecules foreign to biological systems - on male fertility was first recognised in the 1970s, when male workers who had been directly exposed to an agricultural pesticide, 1,2-dibromo-3-chloropropane, suffered severe disruption of sperm development, says Professor John Aitken, the director of the Centre of Excellence in Biotechnology and Development at Newcastle University.

More recently, genital abnormalities have been found in male alligators in Florida swamplands where the poisonous chemical DDT has been tipped. In Ontario, male mice breathing unfiltered air on a highway downwind from two steel mills developed

60 more DNA mutations than mice that breathed filtered air - a pointer, some scientists believe, to the potential environmental impact of heavy industry on men's fertility.

Mobile phone use is also implicated. A preliminary study of 361 men published in January in the journal Fertility And Sterility found the more hours men spent on a mobile phone, the lower their sperm count and the greater their percentage of abnormal sperm. However, researchers were quick to point out they had found only an association, not proven cause and effect.

Aitken says sperm is vulnerable to attack from contaminants both within male germ cells in the mature testis, which make the sperm, and after it has been released into the female reproductive tract because it lacks a protective coating.

Naturally, age may simply weary sperm quality and numbers, given men do have a biological clock. It is not a uniformly sharp decline in natural fertility, but a decline in tissues, nonetheless. Researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, published a study in 2003 of 97 healthy, non-smoking men from which they concluded sperm motility (movement) declines with age. The chance of sperm motility being clinically abnormal was 60 per cent by age 40, and 85 per cent by age 60.

Aitken says that DNA damage in sperm cells increases with age and exposure to environmental contamination such as exhaust fumes. "That has an impact not so much on a man's ability to produce sperm, but to produce normal sperm," he says. "So to give a classic example, if you're a man and you smoke heavily, it doesn't have a dramatic impact on your fertility, but it induces DNA damage in your germ line, and your children have a five-fold increase chance of developing cancer."

In Australia there are concerns with detergents such as nonylphenol, which is used in some household and industrial cleaning products - "but we have no idea what impact it has on male DNA quality" - as well as microwave radiation from mobile phones. Preliminary data suggests eating unsaturated fats - as opposed to saturated fats, which are bad for the heart - causes problems in male DNA germ lines, Aitken says.

Separately, Aitken and colleagues also suggested in detail in another paper in Nature back in 2004 that pregnant women exposed to xenobiotics passed on testicular dysgenesis syndrome, which has features including poor semen quality and testicular cancer, to their male offspring.

How this happens is also very uncertain. But epigenetic modification - in which small chemical tags are attached to the DNA, altering the activity of nearby genes - may hold fresh though sobering answers.

In 2004, Monash Institute of Medical Research scientists in Melbourne knocked out a gene that was an epigenetic regulator in breeding mice. "The mice were born, they looked fine, but the males were all infertile," recalls researcher Moira O'Bryan. "That wasn't what we were expecting."

At Washington State University, a team led by Michael Skinner reported in the journal Science in 2005 that female rats exposed to vinclozolin, a fungicide used in vineyards, and methoxychlor, a pesticide, produced males with low sperm counts - likewise the grandsons and great-grandsons.

In human studies published last December, scientists at the University of Southern California in the journal Public Library of Science One also suggested epigenetic changes trigger male infertility. They found sperm DNA from men with abnormal or low sperm levels had high levels of methylation, while normal sperm samples showed no methylation abnormalities. "Exposures to chemicals as a foetus may lead to adult diseases," suggested author Rebecca Sokol.

Matthew Anway of the University of Idaho told the American Association for the Advancement of Science annual meeting in Boston in February that garden chemicals caused rats inheritable problems such as damaged and overgrown prostates, infertility and kidney problems, which were present up to four generations later. He, too, had pinpointed vinclozolin exposure as a cause of female rats producing infertile sons via epigenetic modification.

But the conference was reminded that fathers might also pass on health problems to their children, via the more traditionally understood mutation of the male germ line. Another scientist, Cynthia Daniels of Rutgers University in New York, warned both would-be parents to stay away from unnecessary chemicals, but made a point of addressing budding fathers: "If I was a young man I would not drink beer, I would not be smoking when I'm trying to conceive a child."