Sunny Hostin is a legal analyst on CNN's "American Morning."

May 8, 2008

NEW YORK (CNN) -- There's a courthouse adage: A person who represents himself has a fool for a client.

When a defendant utters those tragic words, "I'm going to represent myself," judges blanch, attorneys snicker, and even the court reporters grimace. I've been on the opposite side of those who have chosen to represent themselves. It wasn't pleasant.

Since 1975, when the U.S. Supreme Court held that the Sixth Amendment "grants to the accused personally the right to make his own defense," many defendants have decided to take the law literally into their own hands.

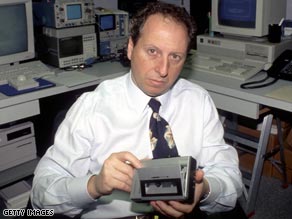

The most recent self-represented "client" is Anthony Pellicano, the Hollywood private investigator who's been on trial for 78 counts lodged against him and two co-defendants.

Pellicano's jury has been out for a week, so it's not yet clear whether the outcome of his case will follow the conventional wisdom.

The 64-year-old celebrity sleuth is accused of leading a criminal enterprise that raked in more than $2 million by illegally spying, allegedly using wiretaps and law enforcement databases, on Hollywood's rich and famous. He then dished the dirt to their rivals.

If convicted of leading a criminal conspiracy, known as a RICO charge, he could spend up 20 years to life in prison. RICO, by the way, stands for the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act. It's the law the Justice Department used to bring down the mob.

Prosecutors have to prove that Pellicano and his co-defendants ran a corrupt enterprise that profited from information they obtained illegally.

U.S. District Judge Dale Fischer granted Pellicano's request to represent himself, but she wasn't too happy about it. "If the U.S. Supreme Court didn't require me to let defendants represent themselves, I wouldn't do it," she said.

Even without a law degree, Pellicano seemed to realize that getting the jury to acquit him of the conspiracy charge was important. During his 15-minute closing argument, he denied he led a criminal enterprise and insisted that he acted as a "lone ranger" while gathering information for his clients.

He also told the jurors that he shared no information with colleagues as he conducted investigations and allowed others to learn only what he wanted them to know. "There was no criminal enterprise or conspiracy. Mr. Pellicano alone is responsible. That is the simple truth," he said, referring to himself in the third person.

But unlike a seasoned attorney, he failed to address the evidence against him, including illegally taped conversations. Instead, he bragged about his career, while wearing an orange prison jumpsuit, saying of himself, again in the third person: "Perhaps his business card should read, 'I deliver,' because he did it over and over again." Courtroom observers said his "cross-examination" often consisted of little more than settling old scores.

So is Pellicano a fool, or absolutely brilliant?

Well, if history is our teacher, he would do better if he had a lawyer, even a bad one. If you have a bad lawyer and you get convicted, you can always argue on appeal that your lawyer was ineffective and get a new trial.

The following self-appointed lawyers learned the hard way that they had fools for clients:

In fact, I can't think of a defendant who represented himself or herself as well, or better, than a lawyer. So maybe I'm biased, but lawyers are trained professionals.