'I practically told the jury to find him guilty'

Globe writers take us back to the days when judges wanted

Henry Morgentaler behind bars but jurors simply refused

ERIN ANDERSSEN AND INGRID PERITZ

From Saturday's Globe and Mail

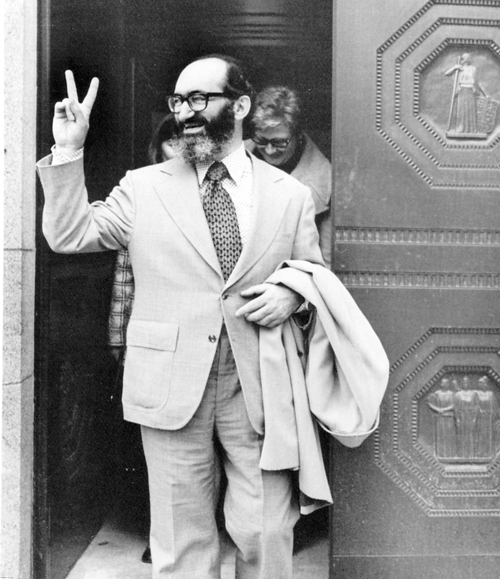

Dr. Henry Morgentaler at his Montreal clinic in 1974.

July 4, 2008 at 10:22 PM EDT

In October, 1984, Susan Bishop sat among the jury pool in a Toronto

courtroom, listening to some of the people around her openly trash the man

whose fate they might soon be asked to decide.

To that point, Ms. Bishop, then 36 and an engineer with Nortel, hadn't

felt strongly about being on the jury. She had a big project due at work,

and generally saw the legal system as costly, inefficient and tangled up in

politics.

But the stage whispers shocked her: These people were on a mission to

convict Henry Morgentaler without even hearing the evidence.

Ms. Bishop didn't have strong views, either way, on the subject of

abortion. To her knowledge, none of her friends had undergone one. She

figured that made her the ideal juror, someone who could approach the case

with an open mind.

“It became clear to me that there were a lot of people who had biases and

strong opinions, and listening to that made me realize I had a role.”

In the end, she was one of the 12 who chose – after less than a day of

deliberation – to acquit Dr. Morgentaler and two other doctors of performing an

illegal abortion. The trial gave her a new faith in the legal system: Each

member of the jury, including six Roman Catholics under heavy pressure from

family members who opposed abortion, ultimately came to a verdict based on the

evidence, she says. For her, the case was an education. She says she realized

how many women were affected by the restrictions then in place, how the system

created an inequality for poor or rural women whose options were more limited.

“We felt confident we were doing the right thing.”

Their decision, following three acquittals by juries in Quebec, would

ultimately send the case to the Supreme Court of Canada, which struck down the

country's abortion law.

But the divisive and emotional opinions that Ms. Bishop witnessed in the

courtroom nearly 25 years ago were fired up again this week with the

announcement that Dr. Morgentaler will receive the Order of Canada, the

country's highest civilian honour. Even as many Canadians praised the decision,

declaring it a fitting honour for a national hero, a Vancouver priest returned

his own award in protest. The Canadian Family Action Coalition, a Christian

grassroots organization, demanded that the government “terminate” the

appointment.

The controversy comes as no surprise to Morris Manning, the Toronto lawyer

who represented Dr. Morgentaler at his 1984 trial and then at the Supreme Court.

But he is disappointed that critics persist in “vilifying” a man who survived

Auschwitz, was willing to go to jail for his convictions and risked his career

for what he believed was right. “He should be recognized for the courage he

showed.”

The fierce blend of support and outrage on exhibit today has dogged Dr.

Morgentaler since he began performing abortions in his east-end Montreal clinic

in the late 1960s.

“We were surrounded by enemies, by people who didn't share our point of

view,” recalls Claude-Armand Sheppard, the doctor's defence lawyer at the time.

But even in the midst of the protests, a judicial pattern emerged, beginning

with the first trial in 1973: Juries listened patiently to the prosecution's

case against Dr. Morgentaler. They heard the investigating officers describe how

the clinic, far from being a house of horrors, had couches, flowers and music

playing. And they refused to convict.

In 1975, the second jury deliberated a mere 55 minutes before the foreman, a

26-year-old meat-truck driver, announced the not-guilty verdict.

The jurors even went against their legal instructions, recalls the Quebec

Superior Court judge who heard the case. “I practically told the jury to find

him guilty,” says Claude Bisson, now retired. “Sometimes laws precede public

opinion; sometimes they follow.”

By then, however, in a legal quirk, Dr. Morgentaler was already serving a

jail sentence – his first acquittal had been overturned on appeal and replaced

with a guilty verdict. In 1975, the Criminal Code was changed so that a jury

verdict could not be treated this way, what is now known as the Morgentaler

Amendment. After he was released, the province went back to court for a third

time; the jury acquitted once again, essentially settling the matter in Quebec.

The controversy skipped west to Ontario when Dr. Morgentaler opened his

Toronto clinic and brazenly invited the police chief to visit. Protests began in

earnest; a volunteer who escorted women in and out of the clinic reported

picking up the phone at home to hear babies crying. Mr. Manning remembers that,

when Dr. Morgentaler took the stand in Toronto, “you could feel the tension

rising, the hatred from some of the spectators.” When his case reached the

Supreme Court, metal detectors were used for the first time.

The complexity of the issue was particularly obvious to Alan Cooper, the

Crown prosecutor in the 1984 trial and now a judge with the Ontario Court. His

office was bombarded with thousands of letters from anti-abortionists urging him

to be vigilant in his duty. Meanwhile, his own friends – even his parents –

wondered how he could prosecute a man they saw as a hero.

“They couldn't accept the fact that it wasn't your personal belief, that you

could actually approach it objectively as a lawyer,” he says. “That's why

abortion can't be the subject of legislation – because it's too closely entwined

with human feelings.”

His argument for the Crown, he says, was made strictly on legal grounds: A

law had been broken. But watching the jury, he recalls today, he knew his case

“was going nowhere.”

As for the Order of Canada, he says Dr. Morgentaler “was a brave guy,

considering the things that have happened in the United States and in Canada.

He's pretty fearless. … I never felt he was in it for the money, and I think he

took enormous personal risks to do what he did.”

So now, Mr. Bisson – three decades after trying to prompt a conviction and

nine years after he himself was named to the Order of Canada – finds himself

welcoming the accused as a fellow member. “You have to be philosophical in

life,” he says. “I am an officer of the Order of Canada, and I respect all those

who are part of that.”

And for Susan Bishop, who avidly followed the court rulings as they led to

the Supreme Court, the honour is long overdue. She remembers listening as

witnesses described how poor women could not afford to fly to hospitals that

were willing to perform abortions, or how delays in the old system meant many

women had to wait too long for the procedure.

“I don't think there are very many people who have sacrificed the way he has.

There's a lot of risk he has taken on, his family has taken on.”

Mr. Sheppard, the lawyer, puts it this way: “Do you know many Canadians who

succeeded in changing the law so completely? The Order of Canada isn't being

awarded to abortion. It is being awarded to an exemplary man.”

Erin Anderssen is a Globe and Mail feature writer in Ottawa. Ingrid Peritz

is a member of the paper's Montreal bureau

Source