MICHELLE SHEPPHARD

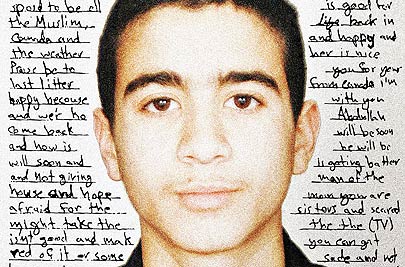

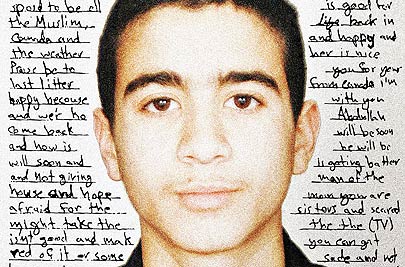

The first time Omar Khadr was questioned, he was lying in a military hospital bed in Afghanistan with two gaping holes in his chest – the exit wounds of the bullets that were shot through his back before his capture by U.S. Special Forces.

Interrogators at the Bagram U.S. Military Base kept one eye on the 15-year-old Canadian while watching the beeping and buzzing machines to which he was attached.

"We asked him a few biographical questions and it was really neat. I know this sounds sick, but it was neat in the sense that you could see his pulse elevating on the machine and his respiration increasing if he got nervous," former U.S. soldier Damien Corsetti said in an interview. "We're taught to see the signs of it physically but you can (normally) never really see it actually happening on the monitor in front of you."

Khadr was a prize captive. He grew up with many of Al Qaeda's elite, had been hiding in Pakistan's lawless tribal region where they had fled, and possibly knew about upcoming attacks. It wasn't yet a year after the 9/11 attacks, and intelligence agencies and the military wanted to know what he knew.

That questioning in August 2002 was the first in a series of interrogations with the Toronto teenager that lasted for more than two years. In Bagram alone, he was interviewed more than 40 times, often for eight hours a day.

Over three separate weeks at the Guantanamo Bay detention camp in 2003 and 2004, Canadians asked the questions. Then they provided Khadr's answers to the U.S.

Revelations Thursday that a Canadian foreign affairs official knew Khadr had been subjected to a sleep deprivation regime the U.S. military calls the "frequent flyer program", and that Khadr told the Canadians he had been tortured and was scared of his American captors, raise new questions about Canada's legal liability and moral responsibility.

What Khadr told his interrogators is also expected to be key evidence at his October military trial in Guantanamo. The Pentagon has charged him with five war crimes, including murder for the death of Delta Force soldier Christopher Speer. Khadr is alleged to have thrown the grenade that fatally wounded Speer during a firefight in Afghanistan on July 27, 2002.

The following reconstruction of Khadr's interrogations is based on interviews conducted over the past two years with more than a dozen sources, which include former detainees who knew Khadr, interrogators who questioned him, and prosecutors now trying him. It also includes an examination of hundreds of pages of court and government records and the statements made by Khadr himself.

Sgt. Joshua Claus was a slight, blond soldier with little experience and lots of responsibility when he became Khadr's interrogator in the cavernous U.S. prison in Bagram detainees nicknamed "The Barn."

Claus would later be convicted for his role in the death of another detainee at Bagram – an innocent Afghan taxi driver named Dilawar. Claus pleaded guilty to maltreatment and assault in return for a five-month jail sentence in 2005. The 2,000-page confidential army file on the investigation into the case, obtained by The New York Times, quotes another soldier saying that Claus twisted a hood over Dilawar's head the day he died. "I had the impression that Josh was actually holding the detainee upright by pulling on the hood."

During the only interview Claus has granted, he told the Toronto Star any allegations of Khadr's mistreatment were false. "They're trying to imply I'm beating or torturing everybody I ever talked to," Claus said.

"Omar was pretty much my first big case," Claus added. "With Omar, I spent a lot of time trying to understand who he was and what I could say to him or do for him, whether it be to bring him extra food or get a letter out to his family ... I needed to talk to him and get him to trust me."

Khadr also described his interrogations, but the U.S. Department of Defense has censored some of the details in his sworn affidavit.

"During this first interrogation, the young blond man would often (censored) if I did not give him the answers he wanted," Khadr claimed. "Several times, he forced me to (censored), which caused me (censored) due to my (censored). He did this several times to get me to answer his questions and give him the answers he wanted."

Later he writes: "I figured out right away that I would simply tell them whatever I thought they wanted to hear in order to keep them from causing me (censored)."

Guantanamo prosecutors initially claimed that Claus (who is identified in court documents only as Sgt. C) would be a key witness at Khadr's military trial. They've recently changed their position.

"The government was confident we could prove our case beyond a reasonable doubt without Sgt C's testimony," prosecutor Marine Major Jeff Groharing wrote in a recent email to the Star. Khadr's lawyers plan to argue that Claus abused the Canadian teen and that threat of harm overshadowed any subsequent interrogations, making anything Khadr said unreliable and inadmissible for his trial.

At Guantanamo, three months after his capture, Khadr's interrogations began again in a military hospital. Still recovering from his wounds, he claims in his affidavit the first interrogators spoke to him for about six hours over two days.

"One interrogator was in civilian dress clothes and I think he told me he was with the (censored). The other was in military camouflage. They asked me questions about everything. I don't think there was anything new."

British detainee Ruhal Ahmed used to watch Khadr come and go. Sometimes Khadr would be excited and tell Ahmed about all the things his interrogator had let him do – like watch Hollywood movies, or eat candy, Ahmed said in an interview from Britain, where he now lives. Sometimes, Ahmed said, Khadr would return to his cell, put his blanket over his head and sob.

Khadr claims in his affidavit that during various interrogations at Guantanamo he was threatened with rape, extradition, he was hit, or left shackled for hours. "A military official then removed my chair and short-shackled me by my hands and feet to a bolt in the floor," he claimed about one interrogation. "Military officials then moved my hands behind my knees. They left me in the room in this condition for approximately five to six hours, causing me extreme pain."

During a December 2002 interview, the prosecution states Khadr told interrogators he "vowed to die fighting" in Afghanistan on the July 2002 day he was captured. He also told them he armed himself with an AK-47 assault rifle, put on an ammunition vest, and positioned himself by a window near the compound, according to a government court document.

Guantanamo's chief prosecutor, Army Col. Lawrence Morris, told the Star the prosecution plans to enter "into evidence certain statements made by Omar Khadr."

The Military Commissions Act under which the trial is governed forbids the use of evidence gleaned under torture. But the rules allow evidence "in which the degree of coercion is disputed," if the military judge finds the information is "reliable" and "in the interests of justice." Critics say this allows evidence obtained under what they call "torture lite."

The Canadian spy who interviewed Khadr in February 2003 was a senior agent working out of the Toronto office of the Canadian Security Intelligence Service and had followed the Khadr family for years (the Star is legally prohibited from disclosing the agent's name).

Jim Gould, a now-retired foreign affairs official who worked for the department's intelligence section, accompanied the agent on the interview but did not speak. He would return a year later to meet with Khadr alone.

Gould would not comment this week, but in interviews given last year, he said that, over the week of interviews with the CSIS agent, Khadr's demeanour changed dramatically. "The first day we brought a Big Mac. It was just inhaled, like any teenager who hasn't had a hamburger in six months," Gould said.

"Second day he declared he had been tortured, tore his shirt off to show us how."

In his affidavit, Khadr describes his disappointment in the Canadians. "I was very hopeful that they would help me. I showed them my injuries and told them that what I told the Americans was not right and true. I said that I told the Americans whatever they wanted me to say because they would torture me," Khadr stated in his affidavit. "(But) the Canadians called me a liar and I began to sob. They screamed at me and told me that they could not do anything for me. I tried to co-operate so that they would take me back to Canada. I told them I was scared."

When Gould returned by himself in March 2004, he was less interested in gleaning intelligence from Khadr, he said, but more concerned with learning about Khadr's beliefs. "I met him two days for an hour-and-a-half each time. He was just playing with me. `You get me back to Canada and I'll tell you everything you want to know. You give me this and I'll tell you everything you want to know,'" Gould said. "In his eyes, (there was) recognition that he was playing. I think he had been hardened in that year since I'd seen him."

Khadr claims Gould told him: "I'm not here to help you. I'm not here to do anything for you. I'm just here to get information."

What wasn't known until this week, when the government handed over uncensored portions of a 2004 Foreign Affairs document, is that Gould was told by a U.S. soldier that to "prepare" Khadr for the visit, the then-17-year-old had been subjected to the military's "frequent flyer program." This meant that, for three weeks, Khadr had been moved from cell to cell, never allowed to sleep for more than three hours.

The sleep deprivation was intended to make him more willing to talk. But international law, and even the U.S. Army's own rules, classify this method as "mental torture."

Canadian Federal Court Justice Richard Mosley wrote in a ruling last month that the practice described to Gould was a "breach of international human rights law."

"Canada became implicated in that violation," Mosley wrote, when Gould "chose to proceed with the interview."

Michelle Shephard is the Star's National Security Reporter and author of Guantanamo's Child: The Untold Story of Omar Khadr, which was published this spring.

Commentary by the Ottawa Men's Centre in the Toronto Star

Thankyou Michelle

Brainwashed Children

not published

Canada deported Khadr knowing he would never get a fair trial in an American justice system that makes political not legal decisions. Its a "Canadian Judicial Trend". Flagrant Canadian Judicial abuse results in many Canadian Father's being effectively deported from Canada under threat of indefinite repeated incarceration or arrest on fabricated criminal charges for the "political offense" or seeking to enforce their children's rights to a relationship with both parents. www.OttawaMensCentre.com