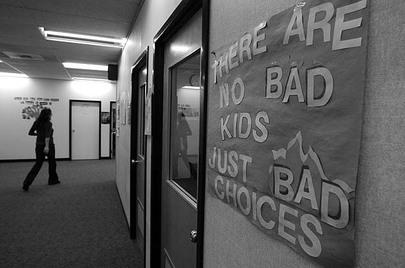

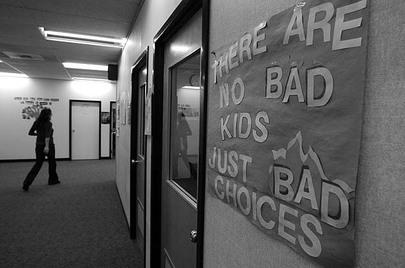

Expulsion School: In Limbo Sandro Contenta and Jim Rankin document life inside a Toronto District School Board program for expelled students, who must prove themselves in order to return to normal school. There are fears the expectations are too high. Part of a series. Stories and interactive graphics at www.thestar.com/suspend.

Toronto principals are finding loopholes to get rid of problem students and circumventing legislation designed to have the opposite effect, the Star has found.

A little more than a year after Ontario ended "zero tolerance" in schools a practice that saw tens of thousands of students thrown out yearly for misbehaviour a Star investigation of the law that replaced it found several questionable practices.

Some suspensions, meant to be brief, are lasting months. Other students are being "excluded" informally so they don't show up on school board statistics. Lawyers are increasingly involved, dragging out disciplinary fights while students linger in limbo.

For those formally expelled the most serious form of discipline principals are often setting conditions so high for their return to regular school that the students are effectively being thrown out for the rest of their high-school years.

"We are turning into an alternative program where we're going to be warehousing students that can't get their expulsion lifted," says Tim Iacono, a teacher at a school for expelled students run by the Toronto District School Board.

Those expelled are being offered, as the new law requires, alternative programs like Iacono's. But some students enter a suspension limbo.

One 16-year-old, for example, was suspended 19 days for smoking marijuana. Yet he spent almost five months out of regular school before his lawyer and mother pressured the board to find a suitable one for his return.

"They just pretend like the kid doesn't exist," said the youth's lawyer, Selwyn Pieters, who specializes in suspension and expulsion cases.

No one expected these outcomes when the Liberal government changed the law on suspensions and expulsions in February 2008. It was applauded for tempering a hard-line approach criticized as targeting students with learning disabilities, from low-income families and from some racial groups.

Continuing to get discipline wrong and failing to treat problems early can have costly consequences for crime and other social problems. High-suspension regimes in the United States have been dubbed the "school-to-prison pipeline."

A Star analysis shows Toronto schools with the highest suspension rates tend to be in areas that also have high incarceration costs. The findings combine school suspension rates for 2007-08 with a snapshot of sentences and postal code data for inmates in Ontario's provincial jails, obtained by the Star through a freedom of information request. (See accompanying map.)

Before last year's reforms, schools washed their hands of most students thrown out a number that peaked at roughly 23,000 six years ago for the two Toronto boards combined. Last year, almost 13,000 were suspended; a further 202 were expelled by the TDSB.

Now, school boards must offer alternative programs for anyone banished for more than five days. Students praise the small classes and extra help these programs provide.

But only one in 10 suspensions in the TDSB is long enough to qualify for an alternative program. Even then, only half of students suspended for six to 10 days take up the offer of alternative programming.

And the program's effectiveness can be undermined. Some principals and teachers fail to provide the students with course work to bridge their entry into the programs. And students from schools where they study eight courses for the whole year can be sent to expulsion programs where they can study only four per semester virtually assuring failure in at least four courses unless the expelling school provides a study program for the rest.

"But the school doesn't want anything to do with him any more because they just expelled him. And the teachers don't want anything to do with him because they go, `He's not ours any more,'" says Chris Wiggins, a guidance counsellor who works in three expulsion programs.

Students can also lose weeks of schooling while lawyers battle over their futures. Parents are more likely to turn to lawyers for help under the new law.

The old law limited expulsions to one school year. Now, expulsions are indefinite all the more reason for parents to fight them, particularly since returning to regular school is proving difficult.

One student now in a Scarborough expulsion program on Midland Ave. which the Star spent seven days monitoring was suspended, pending expulsion, last November. His parents contested the move to expel and kept him home. His expulsion hearing was repeatedly postponed as lawyers argued over evidence and procedure.

He voluntarily joined the Midland program in February. His behaviour is consistently positive and he's on track to getting six of eight credits. But his expulsion was only officially confirmed three weeks ago.

He can't go back until he satisfies the criteria in an Expulsion Student Action Plan (ESAP), assigned by the expelling principal. That hasn't been drafted yet. So he will return to expulsion school in September.

All expelled students must satisfy their ESAP before returning to regular school. Typically, principals set four criteria: regular and punctual attendance; three months of positive behaviour; participation in non-academic programs such as anger management and a demonstration, for example, an ability to respect authority; and earning credits consistent with a regular school, which means passing at least three of four courses a semester.

Some students change the behaviour that got them thrown out but can't meet the academic standards for return. And yet, the Education Act does not cite poor grades as a reason for suspension or expulsion.

"I'd like to have more of a rapport with the principals writing these things because some of our students, we're seeing the best that they're capable of producing but it's not good enough to get their expulsion lifted," says Iacono, who teaches English at the Midland Ave. program. "What some of the principals and (teaching) staff are actually trying to do is just get rid of this student," says Koryn Marshall, a Toronto youth worker.

Between February 2008 and April 2009, only 29 per cent of students who participated in a TDSB expulsion program returned to regular schools. Fifty-four per cent were still in the program while 17 per cent withdrew, entered a treatment centre, or are in custody.

Education Minister Kathleen Wynne said students should not be kept in expulsion programs because of academic problems.

"The legislation allows for there to be criteria that the kids have to meet before they can come back into the mainstream, but there shouldn't be academic barriers," she said.

School boards should provide programs that support formerly expelled and suspended students academically once they're back in regular schools, she added.

Indeed, there are signs that some students who succeed in the expelled programs are returning to low grades and disruptive behaviour once back in the mainstream. It's feared they're the victims of what staff in alternative programs suggest is the system's Catch-22: Many students only get help once suspended or expelled.

"The vast majority of kids do not want to go back" to regular school, says Kelly Duff, youth worker in a program for suspended middle-school students in Scarborough. She recites a common refrain: "I like it here because when I need help, I get it."

Help is crucial because of the long-term social problems associated with high suspensions.

A former director of the United Kingdom prison system, Martin Narey, once put it this way: "Young people excluded from school each year might as well be given a date by which to join the prison service sometime later down the line." And he didn't mean as employees.

The more students are absent from school, the more likely they are to drop out and get into trouble. More than 70 per cent of Canadian inmates did not complete high school, according to a recent study by a federal task force.

The Safe Schools Act, in force from 2001 to 2008, took students out of school. It resulted in a "zero tolerance" approach to bad behaviour. In 2002-03, the number of students suspended in Ontario spiked to 157,436 an increase of almost 50,000 from two years earlier. Almost one in five of those suspended was identified as having a learning disability or special need. The number expelled shot up to 1,786 from 106 in 2000-01.

The "Roots of Youth Crime" report to the provincial government last fall argued that zero tolerance "increased the criminalization of marginalized youth." Critics argued it was targeting low-income and racial minority pupils, particularly blacks. Parents turned to the Ontario Human Rights Commission, which filed a discrimination complaint against the Ministry of Education and the Toronto board.

The Liberal government responded with Bill 212. It gave school boards $44 million to set up alternative programs for suspended and expelled students and to hire 170 psychologists and social workers. Wynne describes the reform as an "attempt to put a greater safety net around kids who are at risk."

The bill pressured school boards to reduce suspensions and expulsions. Principals must consider whether mitigating circumstances, such as a learning disability, racism or bullying, led to unacceptable behaviour. (Suspensions are triggered automatically for having weapons, drugs or alcohol on school property, or for bullying.)

The alternative programs have "given us the ability to go far beyond the mandate of managing the problem and actually looking at the roots of the problem," says Kevin Battaglia, principal of the TDSB's Safe Schools Alternative Programs.

But problems persist. Youth workers and lawyers representing students thrown out of school report an increase in the number being "excluded" a category that isn't reported to the ministry. The method "became attractive to boards who wanted to get rid of students but not attract attention," says Martha McKinnon, executive director of the Toronto-based legal aid service, Justice for Children.

Under the Education Act, principals can formally exclude students they believe present a danger to others. McKinnon estimates her caseload of formally excluded students has tripled in the past year.

Exclusions outside the Education Act are also on the rise, says lawyer Glenn Stuart. They involve, for example, students sent home for a day or two for dress code infractions.

"They don't show up on the stats. It's not a suspension. It's not an expulsion. They're absent missing in action," says Stuart, who works with Promoting Excellence, a program that helps students in the Jane and Finch area stay in school.

Wynne said the ministry doesn't know if exclusions are on the rise. "To the extent that it (is) happening, that's unacceptable," she said.

"I would be dismayed if anyone thought that what we were trying to do is just get the number of suspensions down," she added. "What we need is for students to have real opportunities."

Wynne ruled out new legislation or regulations to fix how the expulsion and suspension law is applied. "What we need to do is continue to assess the reality of the programs and where we see there (are) problems, encourage those practices to stop."