The waters around Cornwall Island are

buzzing with motorboats, but these aren't pleasure cruises or the area's

notorious smugglers.

The boats plying this part of the St. Lawrence River these days are

mostly makeshift ferries hauling commuters across the U.S.-Canada border to

the islands and mainland communities of the Akwesasne Reserve.

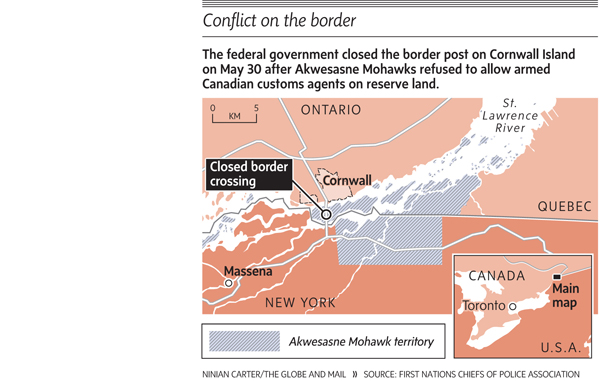

Long-standing animosity between Mohawks and border guards boiled over May

30, when natives protested the arming of customs agents. The guards fled

their Cornwall Island post, saying they feared violence, and the federal

government shut down the crossing. Cross-border travellers now must take

long detours or navigate the St. Lawrence.

A month into the shutdown, there is little sign of tension between

Mohawks and Cornwallites. If anything, they seem united against Public

Safety Minister Peter Van Loan.

Mohawks filed an application last week asking the Federal Court to order

the minister to reopen the border. They have allies among their neighbours.

“I think the minister could make one call and we'd be moving again, but

he won't do it and I don't know why,” said Dennis Fortier, owner of a

Cornwall trucking company. “He's washed his hands of it.”

With the tourist season under way, hotel and restaurant owners are

bracing for a slow summer. Mohawks have also faced difficulties, with

rerouted funeral processions, postponed medical care and disrupted garbage

pickup.

It's barely 3 p.m. on a work day and Mr. Fortier is sweeping the shop

floor and joking with idle truckers. Business is drying up.

Fearing a supply disruption, a U.S. ethanol plant cut orders for crop

byproducts from Cornwall. Ten loads a week has been reduced to one.

Mr. Fortier's business is down about 20 per cent this month. He's losing

about $5,000 a week in revenue. But he has sympathy for the Mohawk position.

“These are good people who are getting a bum rap in all of this,” Mr.

Fortier said. “But the effect is quite devastating. People are getting

afraid, thinking of contingency plans.”

A few kilometres south, in the middle of the St. Lawrence, Liz Sunday, a

62-year-old Mohawk grandmother, is making the complicated Akwesasne commute.

Instead of driving over the Seaway International Bridge, Ms. Sunday

travels from her Quebec home into U.S. territory at the end of Ransom Road.

Then she hops on a boat for a five-minute ride back into Canada. Without

clearing customs, she hitches a ride to Cornwall General Hospital to visit

her husband, Mitchell, who is recovering from a stroke.

Ms. Sunday embraces the voyage with grace. “I like this, you get to see

people you haven't seen in a long time,” she said. “Maybe they should just

leave [the border] closed.”

A dozen people on the boat say theirs is a principled fight.

“I'm sort of sick of this, but I don't see why the guards should have

guns,” said Niiohontesha Jacobs, 23, U.S.-bound to pick up her two kids from

preschool.

Mohawks warned 18 months ago they would not stand for Canadian customs

agents carrying 9 mm pistols at the only border post on reserve land.

Akwesasne's outgoing Grand Chief Tim Thompson has called Mr. Van Loan a

liar for Ottawa's claim substantive talks were held on the gun issue. A sign

at the border post calls Mr. Van Loan Public Enemy No. 1.

Canadian Border Services Agency officials have met Mohawk leaders, but

the minister has refused to intervene.

“He won't meet with the mayor of Cornwall, for God's sake,” said Chief

Thompson, to be replaced as grand chief by Mike Mitchell next week. Mr.

Mitchell says he “completely” shares Chief Thompson's view on the border.

Mr. Van Loan's office declined interview requests. A CBSA spokesperson

said officials have met “more than 10 times” with Chief Thompson and a

senior bureaucrat has met with Cornwall Mayor Bob Kilger.

At Cornwall City Hall, the tone is less hostile, but Mr. Kilger is

looking past Mr. Van Loan and the CBSA for help.

“I'm starting to think someone like [Indian Affairs Minister] Chuck

Strahl might be of more assistance. Someone a little more attuned to the

history and sensitivities.”

The border post has triggered animosity for decades. Local traffic

accounts for 70 per cent of the 4,000 annual crossings, most by Mohawks.

Mohawks say they have filed several human-rights complaints over guard

mistreatment. One involves a young man subjected to a body-cavity search.

Another is from a woman who says she was forced through an X-ray machine

designed to scan trucks. The cases are unresolved.

“If you are a young Mohawk male driving a decent car, you will be

searched,” Chief Thompson said. “There is systematic harassment and

provocation. My feeling, bottom line, is they're racist. Not all of them,

but there's always some in the bunch to ruin the apples.”

The behaviour of U.S. border guards is exemplary, he said.

But Canadian border guards have their own version of history after two

decades of asking Ottawa to move the border post outside Mohawk territory.

The border post was the first to get bulletproof glass after it was shot

up, according to Customs and Immigration Union president Ron Moran.

Akwesasne's status as a Canada-U.S. smuggling hub adds to the tension. At

the height of the tobacco-smuggling crackdown in the 1990s, guards were

unnerved by red dots trained on them, apparently from laser-sighted weapons.

Mr. Moran says most of the 37 Cornwall Island agents have doctors' notes

saying they cannot go back. And they definitely won't return without their

weapons. “I think it's irreconcilable at this stage,” he said.

The union boss is one of the few defenders of Mr. Van Loan, saying events

took an unpredictable turn. “If you had asked me on the Sunday before it

happened, I wouldn't have thought they could close the office. Nobody paid

enough attention to it to figure out it would get to this.”

The government is reviewing all options, but none of the potential

answers is simple.

Cornwall merchants worry governments will build a new bridge outside the

city to bypass the island.

The border guards and Mohawks suggest Canadian customs be moved to the

U.S. side. Cornwall's mayor believes the move would face insurmountable

legal hurdles.

If the crossing was placed on the Canadian mainland, Akwesasne's Cornwall

Island would become Canadian territory in a customs no-man's land – hardly a

winning formula for the fight against smuggling.