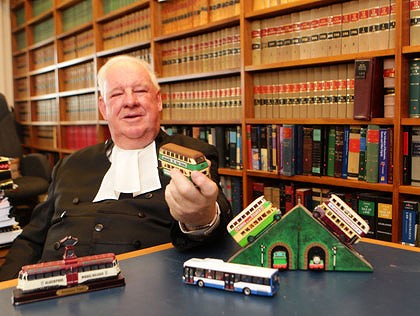

Just the ticket ... Justice Peter Young finds escape in his model bus collection. Ive always been interested. Photo: Brendan Esposito

In rare interviews, the judiciary speaks frankly to Joel Gibson, Deborah Snow, Elisabeth Sexton and Geesche Jacobsen.

Peter Young has been a judge for more than 20 years, but it still chafes that he has to seem antisocial at the most sociable time of year.

''I'm invited to probably about 20 Christmas parties each November and I have to refuse the lot,'' says the NSW Court of Appeal judge, ''because if I go to one, why am I going to that one rather than to the other 19?''

Justice Robert McDougall felt he couldn't join his daughter, an electorate officer for the federal Labor minister Tanya Plibersek, at a fund-raising performance of the musical Keating. ''I really wanted to go but it seemed inappropriate,'' the Supreme Court judge laments.

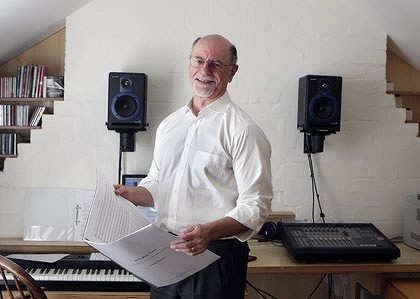

Justice George Palmer in his home music studio.

And the District Court's Judge Peter Zahra finds even kids' sport on Saturday morning can get complicated. ''It's bizarre,'' says Zahra. ''Some of my kids' friends have got parents who are lawyers. You stand there on the sideline watching the footy one week, and then they have a matter before you, and there you are over at the sideline on the other side [the next week] standing there on your own because that person has a matter before you.''

Such is life for those behind the bench, where the professional and the personal can be hard to separate and it is often easier to say hi to a stranger than to a friend you've worked with for 30 years.

As the Herald discovered from talking frankly with 22 of the state's judges and magistrates, the need to avoid the appearance of partiality is always on their minds.

''I have a very close colleague who I haven't now seen for months and won't see for many months more I can't be seen to be having a cup of tea or coffee with him, can't even ring him up,'' says one judge who can't be identified because of an ongoing trial.

Before ruling against old barrister friends, Justice George Palmer jokes, ''You wonder are they going to think, 'Doesn't he like me any more?' ''

Judges and magistrates bristle at suggestions they are out of touch; some sit on community boards, others catch public transport, all confront the nadir of human misery in their courts.

But they are nonetheless destined to move through the world as quasi-outsiders. The price of sitting on the bench is a certain loss of social freedom.

''You've got to abandon not your friendships, but the way in which you manifest your friendships,'' says Chief Magistrate Graeme Henson.

''Those who feel it most are those who identify themselves primarily as lawyers,'' adds Palmer, who cultivates a second life as a classical composer.

For magistrates, who do compulsory country service, and for some District Court judges on regional circuits, the isolation can be geographical as well.

''I've spent many a night in a motel room by myself,'' says Henson. ''You've got to keep your distance and sometimes that can be hard, particularly in the country.''

Women face particular challenges, says Magistrate Daphne Kok. Men can ''go into a bar and say g'day. Most women can't do that. It wouldn't be acceptable in the milieu of a country town.''

Geoff Dunlevy runs the Broken Hill circuit and sits 800 kilometres from his nearest colleague, though paradoxically feels his isolation less than most. ''I sort of enjoy the novelty of being the only magistrate for miles,'' Dunlevy confesses.

Judge Paul Conlon, who moonlights as head of the National Rugby League's judiciary, considers the extreme caution exercised by some of his colleagues to be ''a bit crazy''.

''But it is all this perception stuff. And of course these days everyone is looking for some sort of angle, some sort of dirt.''

The sense of scrutiny is such that Deputy Chief Magistrate Jane Culver, who sentenced Channel Seven news boss Peter Meakin to 14 months of weekend jail for drink driving and driving dangerously, has declined even one glass of wine at social occasions for fear of being seen as a hypocrite.

Some judges and magistrates report receiving abusive letters, although direct threats are rare and attacks extremely so. All judicial officers are given the option of panic buttons and alarms at home which, when triggered, can result in the arrival of tactical response police.

One magistrate reported a bomb being planted on a gas tank at a regional courthouse by a father denied access to his daughter because he nail-gunned her dog to the front door of a house. The magistrate and his family were moved to a hotel until the man was arrested.

''I think I was unlucky. Not many have had experiences like that. I keep touch with what happens with that person. He is still locked up. But the bottom line is that if someone really wants to kill you, as has been shown with Family Court judges, they can.''

And that's just life outside the court. When it comes to sitting behind the bench, the work of a judge or magistrate can be fulfilling and confronting in equal measure. Justice Megan Latham describes it as ''such a singular kind of occupation. No one trains for it. It's not as though you get a probationary period.''

When things go wrong, judicial colleagues rally round but ''at the end of the day you walk on to the bench all alone''.

After being sworn in, says Judge Dianne Truss, ''everyone goes, 'Oh, isn't this lovely' and they all make these nice speeches about how wonderful you are and what a good judge you'll be, and then, bang, here's a case for you.''

When Culver sat for the first time, two judges advised her to place a sticker behind the bench with the words ''You do not object'', lest she relapse into Crown prosecutor mode.

Magistrate David Heilpern has a small plaque on his bench that says ''Remember to breathe''. But he adds, ''I love my job. You go home and feel you have done a little bit of good in the world.''

In recent years, advances in judicial education have eased the transition from player to ''referee'', beginning with pre-bench training or a course known colloquially as ''Baby Judge's School''.

There they do exercises and review statistics to try to bring consistency to sentencing and damages awards. But there is little that can prepare them for viewing images of children used for sex, or for removing a child from his or her family, or for sending a young person to jail knowing it might condemn them to a life of crime.

One of Palmer's first cases as a barrister involved the child of a heroin-addicted prostitute who was stealing. So emotionally draining was it, he decided to specialise in corporate law. As a judge he has now come full circle, overseeing cases involving children and the mentally disabled in the Supreme Court.

''In those lists you are concerned with the raw tragedies of life, the most damaged people,'' he says, his eyes welling. Some days, everyone in his court is in tears.

''The thing that worries me about this job,'' says Zahra, ''is not necessarily the long hours and writing judgments, it's the stuff that gets into your head. And sometimes you can be unlucky because you can have child sexual assault trials back to back.''

Of child pornography cases, the scourge of the internet age, Henson says ''you can't give the same magistrate a number of those cases in a short period of time because I can tell you from having done them myself, they leave you with an indelible memory''.

Even for less abominable crimes, the not-so-simple act of sentencing keeps many judges and magistrates awake at night.

''Particularly,'' says Justice Reg Blanch, the District Court Chief Judge, ''in cases where you would be absolutely certain that the person would never commit another offence at all, so that you could let them go out on the street immediately and know that they'd be no danger to anyone.''

Says Zahra: ''It's the burden of sentencing that really affects most judges.''

For magistrates, it is often bail decisions that cause the most angst. Heilpern explains: ''A lot of people do get refused bail who in the end won't go to jail, and that's at the back of your mind. And the other thing is you might release someone on bail who goes and does something really terrible When that's happened to me there would be 10 people phoning within a day saying, 'Are you OK?', so it's a really terrific place to work like that.''

''You never forget that sort of thing,'' concedes Henson. ''But if you let it take over your life you'll never make a decision.''

All in all, sighs Justice David Kirby, it can mean that being a judge ''makes you much less fun''.

''I hope again once I retire to become jolly in the way that I used to be.''

Some find the bench isolating after the camaraderie of a busy barristers' chambers or solicitors' offices. ''If you let it,'' says Justice Peter Young, ''you would come into your car park, you would go up the judges' lift, you would go into your chambers, you wouldn't see another soul apart from your staff and you would be listening to the most depressing cases between 10 and 4 and that does sometimes lead some guys to drink'' - as it did infamously in the case of the late attorney-general and judge Jeff Shaw. Says Kirby: ''I can remember in my early days at the bar there were judges who notoriously did have a drinking problem. They were sidelined and given work that was less exacting. These days, with the judicial complaints procedures I'm really not aware of anyone who fits the description.''

What comes across strongly is a deep sense of mission among most judges and magistrates. As Megan Latham puts it: ''I don't think there's anyone who does this job who takes a single moment of a single day lightly in terms of the outcomes for the people, the litigants.''