17 August 2011

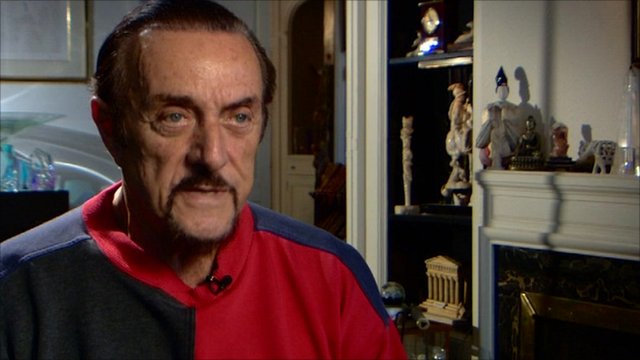

Psychologist Philip Zimbardo and some of the former students who took part recall the experiment

Forty years ago a group of students hoping to make a bit of holiday money turned up at a basement in Stanford University, California, for what was to become one of the most notorious experiments in the study of human psychology.

The idea was simple - take a group of volunteers, tell half of them they are prisoners, the other half prison wardens, place them in a makeshift jail and watch what happens.

The Stanford prison experiment was supposed to last two weeks but was ended abruptly just six days later, after a string of mental breakdowns, an outbreak of sadism and a hunger strike.

"The first day they came there it was a little prison set up in a basement with fake cell doors and by the second day it was a real prison created in the minds of each prisoner, each guard and also of the staff," said Philip Zimbardo, the psychologist leading the experiment.

The volunteers had answered an advertisement in a local paper and both physical and psychological tests were done to make sure only the strongest took part.

Despite their uniforms and mirrored sunglasses, the guards struggled to get into character and at first Prof Zimbardo's team thought they might have to abandon the project.

'Very cruel guard'As it turned out, they did not have to wait long.

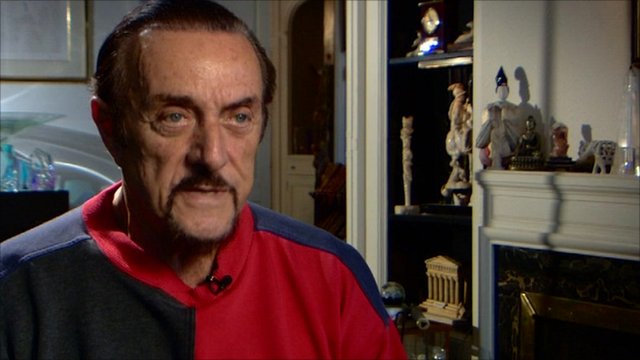

"After the first day I noticed nothing was happening. It was a bit of a bore, so I made the decision I would take on the persona of a very cruel prison guard," said Dave Eshleman, one of the wardens who took a lead role.

The experiment took place in California in 1971

The experiment took place in California in 1971

At the same time the prisoners, referred to only by their numbers and treated harshly, rebelled and blockaded themselves inside their cells.

The guards saw this as a challenge to their authority, broke up the demonstration and began to impose their will.

"Suddenly, the whole dynamic changed as they believed they were dealing with dangerous prisoners, and at that point it was no longer an experiment," said Prof Zimbardo.

It began by stripping them naked, putting bags over their heads, making them do press-ups or other exercises and humiliating them.

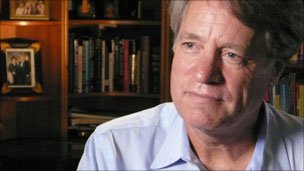

"The most effective thing they did was simply interrupt sleep, which is a known torture technique," said Clay Ramsey, one of the prisoners.

"What was demanded of me physically was way too much and I also felt that there was really nobody rational at the wheel of this thing so I started refusing food."

Power of situations

He was put in the janitor's cupboard - solitary confinement - and the other prisoners were punished because of his actions. It became a very stressful situation.

Dave Eshleman, who played the role of a prison guard said the experiment rapidly spun out of control

"It was rapidly spiralling out of control," said prison guard Mr Eshleman who hid behind his mirrored sunglasses and a southern US accent.

"I kept looking for the limits - at what point would they stop me and say 'No, this is only an experiment and I have had enough', but I don't think I ever reached that point."

Prof Zimbardo recalled a long list of prisoners who had breakdowns and had to leave the experiment. One even developed a psychosomatic all-over body rash.

The lead researcher had also been sucked into the experiment and had lost clarity.

"The experiment was the right thing to do, the wrong thing was to let it go past the second day," he said.

"Once a prisoner broke down we had proved the point - that situations can have a powerful impact - so I didn't end it when I should have."

Prof Zimbardo Psychologist who led the Stanford prison experimentThe experiment was the right thing to do, the wrong thing was to let it go past the second day”

In the end it was a fellow psychologist who intervened.

Prof Zimbardo had been dating Christina Maslach, a former graduate student, and when she saw what was happening in the basement she was visibly shocked, accusing him of cruelty. It snapped him out of the spell.

Prison disturbances in the US drew attention to the Stanford experiment and, all of a sudden, the dramatic results became well known in the US and all over the world.

"The study is the classic demonstration of the power of situations and systems to overwhelm good intentions of participants and transform ordinary, normal young men into sadistic guards or for those playing prisoners to have emotional breakdowns," said Prof Zimbardo.

'Ethically wrong'

The abusive prison guard, Mr Eshleman, also felt he gained something from the experiment.

"I learned that in a particular situation I'm probably capable of doing things I will look back on with some shame later on," he said.

"When I saw the pictures coming from Abu Ghraib in Iraq, it immediately struck me as being very familiar to me and I knew immediately they were probably just very ordinary people and not the bad apples the defence department tried to paint them as.

"I did some horrible things, so if I ever had the chance to repeat the experiment I wouldn't do it."

But prisoner Mr Ramsey felt the experiment should never have taken place as it had no true scientific basis and was ethically wrong.

"The best thing about it, is that it ended early," he said.

"The worst thing is that the author, Zimbardo, has been rewarded with a great deal of attention for 40 years so people are taught an example of very bad science."

But Prof Zimbardo calls this "naive" and argues the work was a very valuable addition to psychology - and its findings were important in understanding why abuse took place at Abu Ghraib.

"It does tell us that human nature is not totally under the control of what we like to think of as free will, but that the majority of us can be seduced into behaving in ways totally atypical of what we believe we are," he said.