June 22, 2016

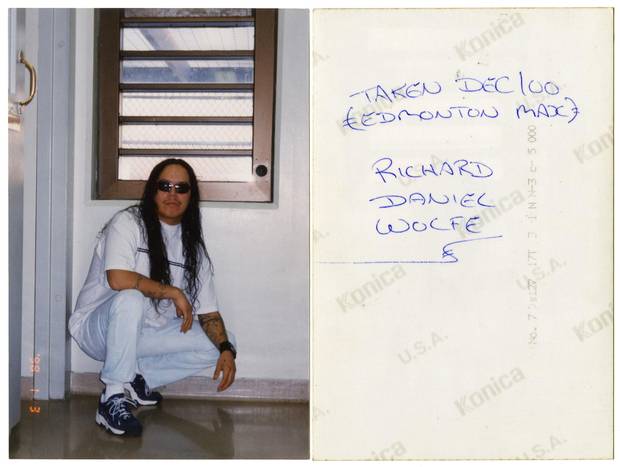

Indian Posse co-founder Richard Wolfe spent half of his life in prison, much of it ‘in the hole’ often with no access to the fresh air and sunshine he is seen enjoying here.

His record was long, his crimes horrific, his guilt uncontested. But as he told Joe Friesen in a remarkable series of letters and phone calls, Richard Wolfe, who died last week in a Saskatchewan prison, was deeply affected by a system that locked him up in solitary confinement

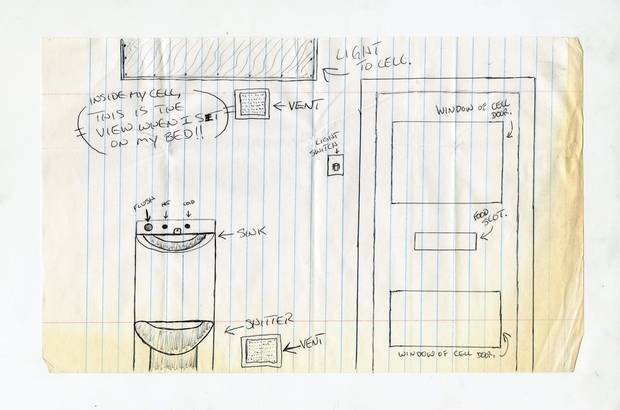

The guards led Richard Wolfe to the segregation unit in April, 2014. They stopped at cell five, considered the most luxurious because it was wheelchair-accessible and slightly larger than the others: 12 feet by 10, Richard guessed. As he stood at the door, he saw a bunk covered by a thin mattress. On one side of the room sat a stainless-steel toilet with built-in sink. Natural light filtered in through a skinny window about six inches high and two feet wide. For the next 21 months – though he didn’t know it at the time – this would be his home.

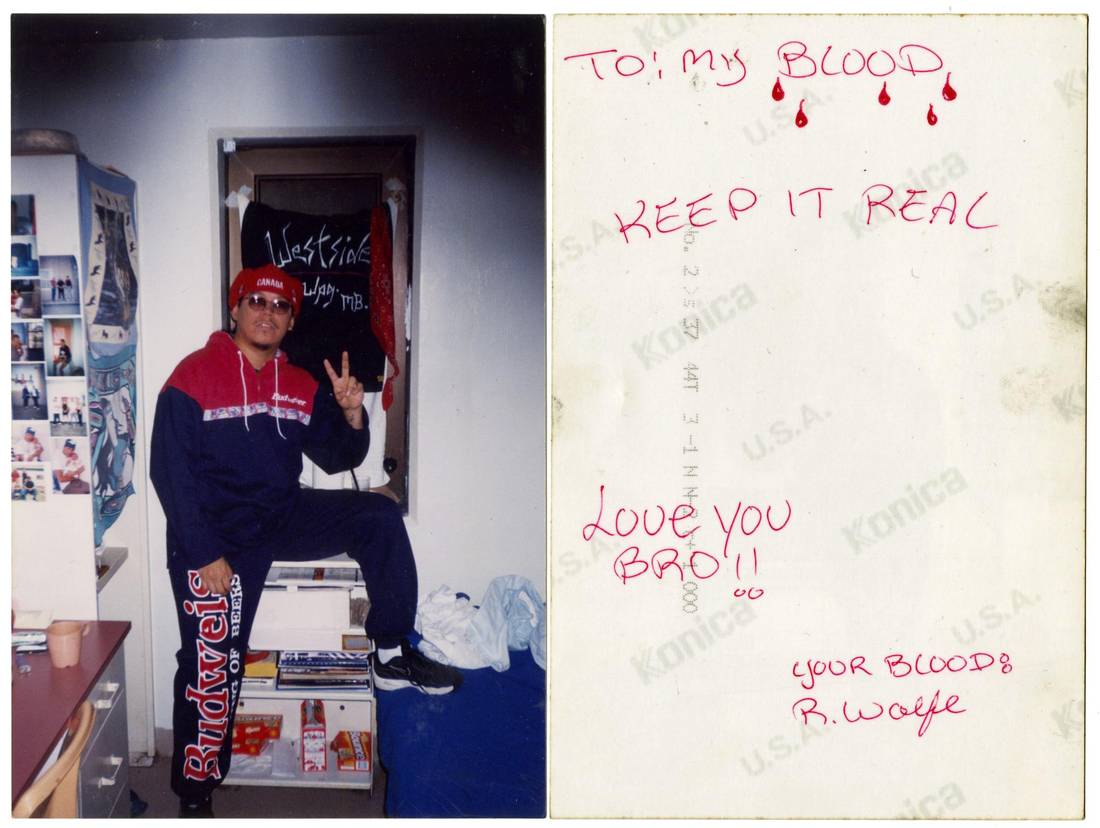

Richard Wolfe at home in 2011 with a photo of his late brother Danny: He had been released nine months earlier after serving 15 years for attempted murder.

From now on, he would not set foot outdoors. His time outside this cell – a single hour each day – would be spent in the “fresh-air room,” an ordinary prison room with cinder-block walls and large windows that can be opened to create a draft.

Richard had no idea whether he would be isolated for a few days, a few weeks or a few months. As time wore on, inmates moved in and out of the unit. Some returned to general population here at the Regina Provincial Correctional Centre, some went to a penitentiary, some went home. Some also crumbled under the strain: They heard voices, screamed for no purpose, cut themselves to escape. They launched hunger strikes, plotted suicides, and railed against the absence of programs. When they returned to the world, Richard stayed behind.

Months dragged as he waited for trial, and then later a presentencing report that would allow the judge to consider options less restrictive than incarceration in cases involving indigenous offenders. In the meantime, Richard was kept in the most restrictive regime possible.

His case posed a difficult problem: As a long-time criminal who had been violent during previous stints in jail, had once founded a notorious gang, and was now in jail for sexual assault, he was a target for other prisoners. If he were placed on a normal range, he might be killed. The system found no better answer than to lock him up alone, indefinitely.

In this sketch, Richard Wolfe detailed the extent of his world at the Regina Provincial Correctional Centre, where he spent almost two years in solitary confinement.

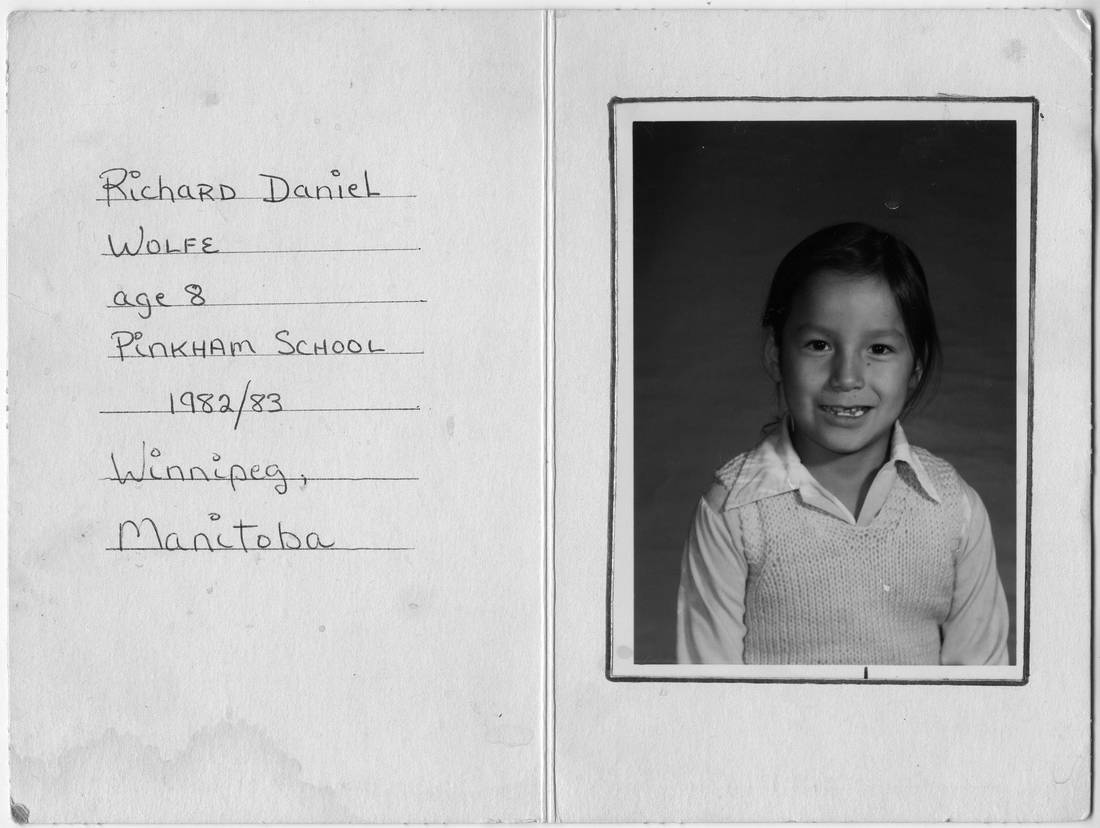

Richard and I met back in 2011, when I began research for The Ballad of Danny Wolfe, a book, about his younger brother, in which Richard plays a prominent part. Richard and Danny co-founded the Indian Posse street gang in Winnipeg in 1988 when Richard was 13 and Danny 12. They dreamed of building a surrogate family to lead indigenous children out of poverty, but the cold reality of gang life eventually consumed them both.

When he was still a teenager, Richard ambushed and shot a pizza deliveryman, and was sentenced to 19 ½ years for attempted murder. After serving 15 years in prison, he was freed on statutory release in 2010.

He moved to Fort Qu’Appelle, Sask., and started a new life. He vowed to live right and got a job harvesting Christmas trees. He moved in with his new girlfriend and her children, and soon the couple had a baby boy.

He got to know his mother and father again, but within a year his father, a chronic alcoholic in failing health, fell into a coma and died. And in 2013 Richard’s girlfriend’s teenage son died in an accident. Richard had been there when the boy died, and tried unsuccessfully to save him after he was crushed by a truck.

After that, Richard said he gave up. He drank and used drugs to dull his pain. His relationship fell apart and he moved out. A local couple offered to let him stay in their basement, hoping he could turn things around. One spring night, after drinking more than a dozen beers and taking several Valium, Richard crept into the woman’s bedroom while her husband slept on the couch, and attempted to sexually assault her.

The woman awoke to the feeling of Richard on top of her, rubbing her. He whispered something, at which point she yelled for help. Richard held her down forcefully and attempted to rape her through the leg of her shorts. Her screams woke her husband, who confronted Richard. Richard grabbed a bat, beat the man bloody, and ran. When he came to his senses, he was covered in the other man’s blood, worried that he had killed someone.

He later phoned to tell me he was on his way back to jail. He said he couldn’t remember the events of the night before, but he’d have to go away for a while. He was driving down a country road in the Qu’Appelle Valley, on his way to the police station where he’d arranged to turn himself in. He was taking one last ride with his son, snapping photographs and listening to music. He wanted to absorb it all, to see one last prairie sunset, because it was all he would have for a long time.

Over the next 91 weeks, Richard regularly wrote letters and made phone calls describing what it was like to be locked in segregation. His account provides a rare glimpse inside a prison regime that is controversial, little known and, according to prominent critics, counterproductive.

The story of Richard’s path to this place will not elicit sympathy; he committed crimes and did serious wrong. He was in prison to pay a price for his actions and because the public had to be protected from him. But the public also assumed responsibility for his safety and his rehabilitation, and the impact of long-term solitary confinement deserves scrutiny.

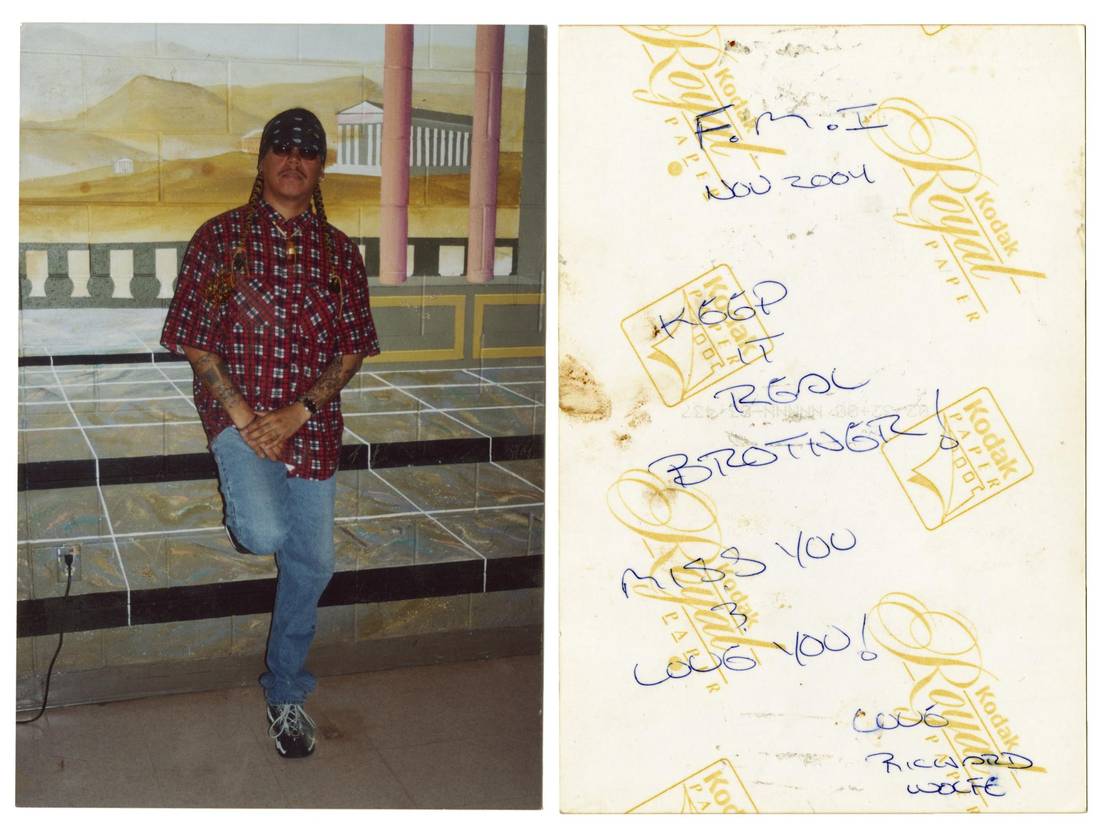

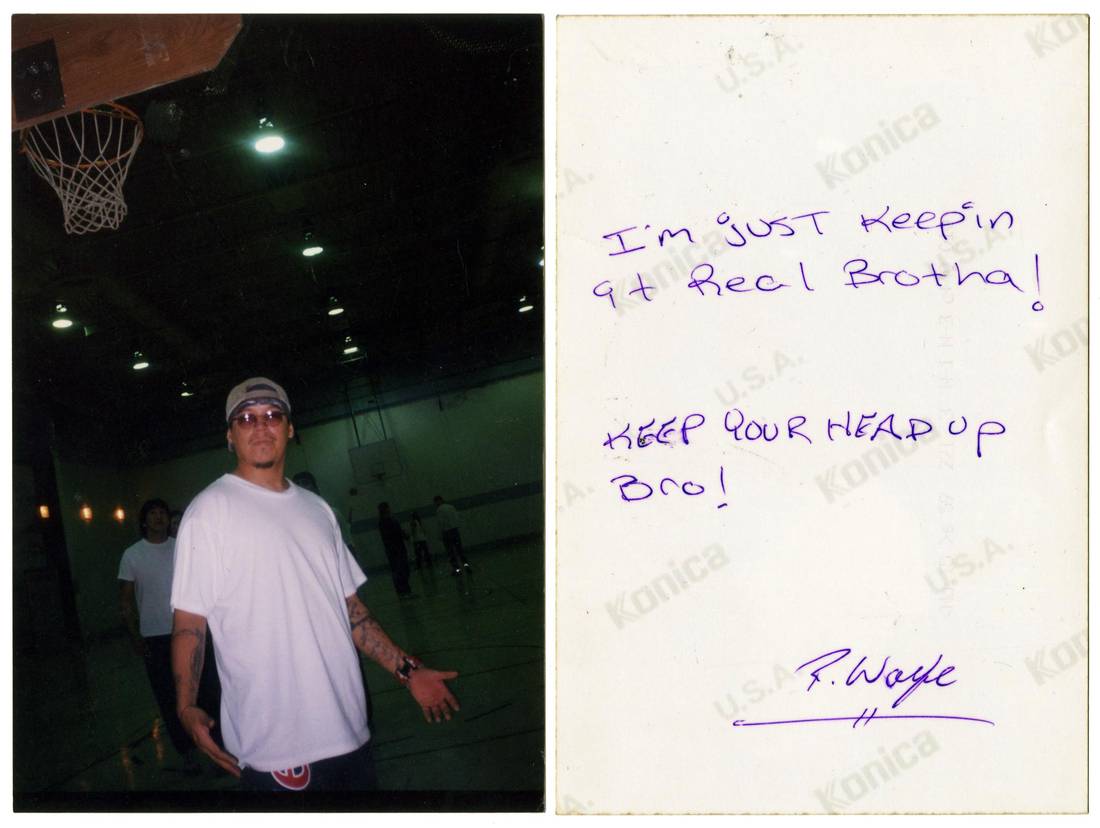

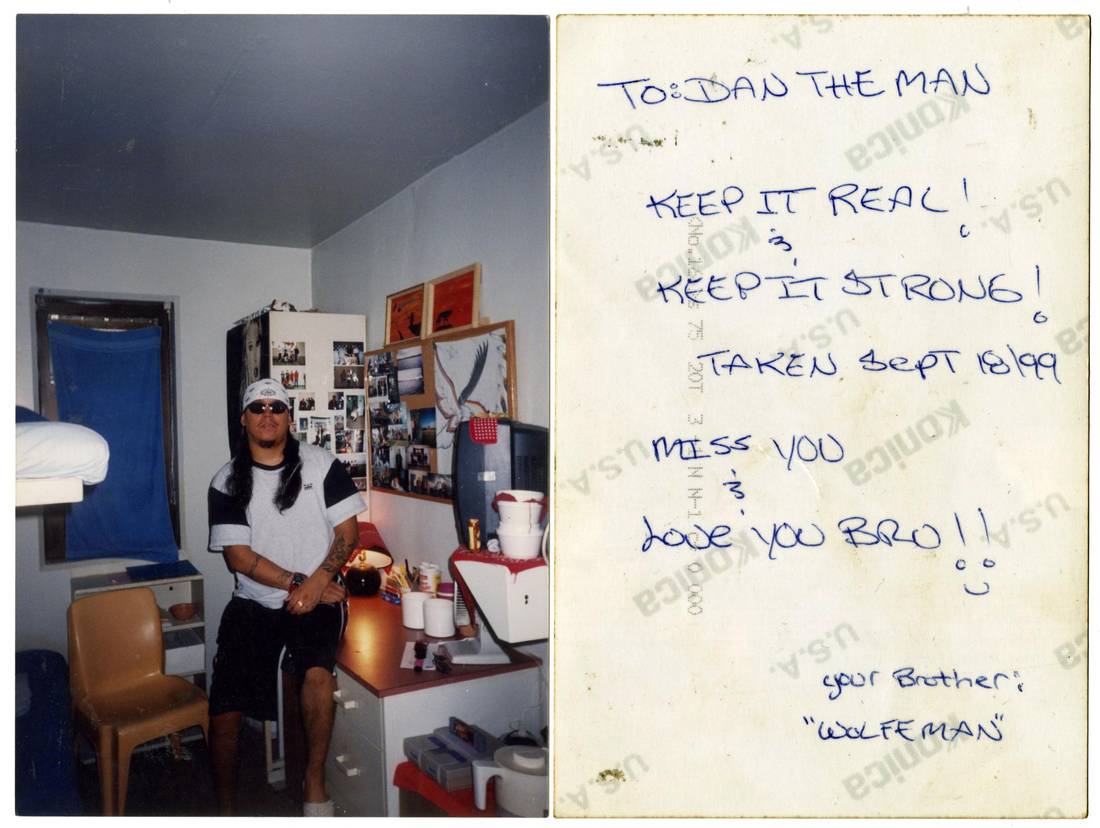

Richard often sent his brother, Danny, photographs with words of encouragement written on the back.

Courtesty of Susan Creeley

From the moment he entered the Regina Provincial Correctional Centre on that April day two years ago, Richard was told he presented a threat to the safety of the institution. He was notified that he would be placed in administrative segregation, otherwise known as 23-hour lockdown. His status would be reviewed every 21 days.

As a founder of the Indian Posse, a large, primarily indigenous street gang, he was a high-profile inmate and a significant target for rival gangs. Although his brother died in 2010, and Richard said he himself had left the Indian Posse more than a decade ago, the Wolfe name remained notorious in Canadian prisons. And, because he faced a charge of sexual assault, the unwritten rules of prison subculture made him vulnerable to attack.

Complicating matters for his jailers, Danny Wolfe had led five inmates on a successful escape from the same Regina jail in 2008, prompting guards to warn Richard not to try anything similar.

Richard donned the bright orange T-shirt and pants that are the uniform of solitary inmates. He was given a towel, socks and one pair of underwear. The underwear could be exchanged in the laundry but, like most other inmates, Richard wouldn’t trade them for fear of getting someone else’s used pair in return. At night he had no choice but to sleep in those same clothes. This is typical for prisoners in Regina, who have complained of developing skin rashes from unclean clothing, according to a 2014 report by the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. His cell was cold at night, so he stashed away an extra towel to drape over his thin blankets.

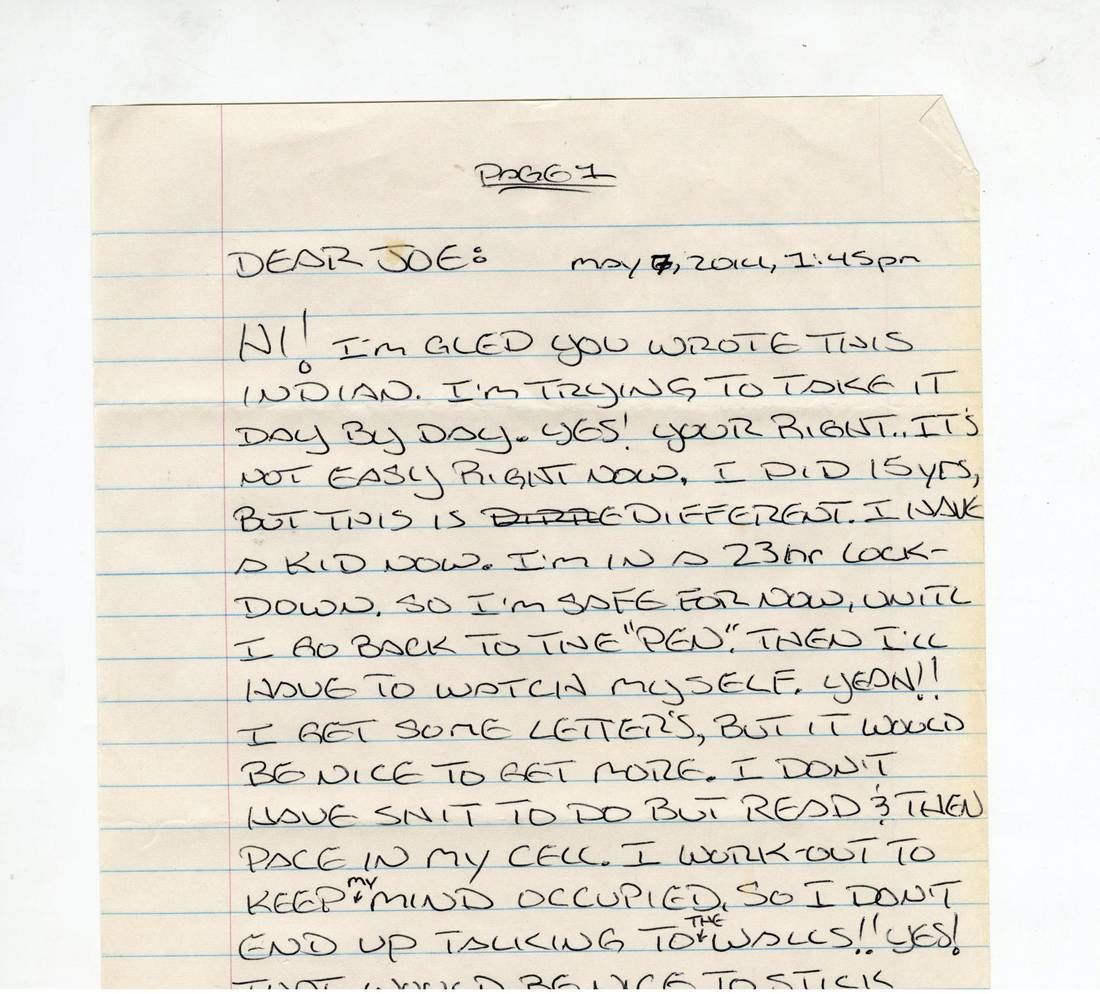

“It’s not easy right now,” Richard said in a letter in May, 2014, a few weeks after he arrived. Once, he had been the one who called the shots, a teenage outlaw who bragged that “brothers do as I say.” Now, at 38, he was an aging former gangster who had proved unable to make the transition to a law-abiding life on the outside. His movements, his associations, his environment were all subject to the control of the institution.

Wolfe wrote to Globe reporter Joe Friesen during his time in administrative segregation

On weekends, his former girlfriend drove down from Fort Qu’Appelle with his son to visit for an hour. Richard would sing the alphabet and play peek-a-boo with his son behind the glass partitions. The boy would ask why he couldn’t come around to his side of the window.

“I always tear up when he leaves. He blows me a kiss. That gets me every time,” Richard said. “[She] tells him I’m at work and I’ll be home soon.”

Richard waited anxiously for letters. He didn’t get many. “I don’t have shit to do but read and then pace in my cell,” he said. His world was reduced to a space he could traverse in three or four strides, five if they were short, sometimes for hours on end.

At first, Richard kept an eye on the clock in the corridor, looking for it every morning when he woke. But there was so much time, and so little to fill the hours; he learned to frame his life in simpler terms – before lunch or after lunch. It was easier that way.

Every prisoner in segregation is allowed one hour each day out of his cell. That’s all the time there is to shower, shave, make phone calls, and exercise. But he couldn’t go outside, couldn’t touch the grass or feel the crunch of gravel underfoot. He was inside and alone, day after day, with little to interrupt the crushing monotony.

The stress of solitary confinement tends to push people one of two ways, experts say: They turn either inward or outward. Those who turn outward tend to act out violently; those who turn inward tend to get depressed. A lot depends on what kind of mental baggage inmates bring with them, and many bear heavy mental and emotional scars.

The academic research on the effects of segregation ranges from studies that show no lasting damage to others that indicate significant long-term harm. The most convincing work, according to Canada’s Correctional Investigator, Howard Sapers, tends toward the conclusion that segregation causes psychological distress.

How that happens, though, differs from case to case. It often begins with disassociation: losing a sense of who you are, or losing a sense of time. Anxiety creeps in, thought processes become muddled, a feeling of hopelessness prevails. Sleep gets disrupted; many inmates stay up all night and sleep through the day. Some former inmates describe talking to themselves or hearing voices, according to Mr. Sapers; others lash out violently at guards, at their cells, or at themselves.

“Almost everybody talks about both anger and fear and frustration and hopelessness,” Mr. Sapers says. “Nobody has ever described positive emotions, except in some instances people have talked about some feeling of safety early in their segregation experience. … That sense of safety vaporizes over time and then the hopelessness and anxiety builds up again.”

You feel really alone. Loneliness, a lot of loneliness. Your thoughts of other things from the outside are totally erased. Your mind is pretty much half taken away.

Audio: Wolfe describes being moved into administrative segregation

Sharon Shalev, a leading expert on solitary confinement at Oxford University, says the extent of the harm, when it occurs, often depends on the length of time in segregation. In a study of British prisoners, Prof. Shalev found that those who had spent more time in segregation reported more symptoms.

And beyond the psychological fallout are a range of physiological effects. Among those listed in Prof. Shalev’s Sourcebook on Solitary Confinement: heart palpitations, cardiovascular problems, profound fatigue and the aggravation of pre-existing medical conditions.

“The UN considers anything longer than 15 days prolonged [segregation], and therefore against international law,” Prof. Shalev says. “Another important factor is whether they know how long they’re going to spend. The literature shows that not knowing how long you’re going to spend in isolation quite seriously exacerbates the effects.”

After a few months, the strain started to show: Richard’s letters to me took on an increasingly frustrated tone. His ex told him they were through, and she wasn’t going to bring his son for visits any more. He was getting death threats from other inmates, and his family was worried about his safety. He said he needed a sweat lodge to help him deal with the ongoing pain he felt over the death of his teenage stepson.

“I’m trying to take it one day at a time. It’s fucking hard right now,” he wrote. “I was foolish and stupid to do drugs and alcohol. To be honest, I never talk to anybody about [my stepson’s] death. We found him and I was giving him CPR. I keep going back to that night. I needed a break from reality. So I end up doing drugs and alcohol.”

Sweat-lodge ceremonies, which take place in a specially built structure on the grounds of the jail, aren’t offered to prisoners in segregation. A large majority of prisoners sentenced to Saskatchewan provincial jails are indigenous (they make up 16 per cent of the provincial population), so the ability to practise their traditional culture is not a fringe concern. The Saskatchewan Ministry of Justice allows cultural and chaplaincy services to be accessed through one-on-one visits, after submitting a request.

Richard watched from his window when the other prisoners entered the sweat lodge on the jail grounds or when they milled around outside. Sometimes he was able to communicate with a cousin, who was being held in general population, by holding up letters in the window (he kept a couple alphabets’ worth of hand-drawn letters at the ready). His cousin would wave back or mime something in reply. It wasn’t much, but it was human contact.

“Solitary confinement fucking sucks,” he wrote in one letter to me. “We get fuck all when [we’re] in the hole.”

In a matter of months, Richard said, he had lost 35 pounds. Part of the reason, he believed, was that inmates in solitary at the Regina Provincial Correctional Centre aren’t allowed to purchase additional food from the prison canteen. He was often hungry.

Food arrived through a slot in the door and was usually unappetizing, he said. Pizza and spaghetti days were the best, tuna salad the worst.

The prisoner who delivers the food trays is known as the cleaner. It’s a coveted job (one Richard would eventually hold) because it comes with tiny amounts of freedom; the cleaner can leave his cell three times a day, and is the main social contact for all the other inmates in solitary.

At that time, the cleaner was a man awaiting trial for allegedly killing Richard’s cousin. They approached one another warily, but Richard was desperate for social contact, and they eventually bridged the tension by exchanging stories about their kids.

“I’m not here to do anybody’s time. I’m just here to do mine and get out to be with my son,” Richard explained to me.

Any kind of exercise equipment was banned, but Richard, determined to stay active to keep himself sane, would roll up his mattress, or fill a garbage bag with water, to create a weight he could curl and press. If he wanted more weight, he would add water to the bag, although he risked getting caught and punished if the bag were to burst.

“I work out to keep my mind occupied, so I don’t end up talking to the walls,” he wrote.

Prisoners have many ingenious ways of communicating, even when they are supposedly isolated. One that Richard described involved draining the water from the toilets and then speaking through the pipes to inmates in cells located on floors above. Another is via “kites” – messages written on tiny fragments of folded paper that get passed by hand through the jail. And people are always shouting through doors and walls, giving the place the echoing ambience of a menacing gym.

“These guys in the [unit] above us are saying I’m a dead man when I get to Sask. Pen [the federal penitentiary in Prince Albert],” Richard wrote. That threat hung over him. Sometimes he played down its significance, dismissing it as “cell champing,” and sometimes he worried.

“A lot of people want to kill me, so they can make a name for themselves by taking out a big name. I don’t look at myself like that, but a lot of people say it’s true, and I’ll have to live with that for the rest of my life.”

The UN special rapporteur on torture said in 2011 that the prolonged isolation of prisoners for 22 hours or more a day should be banned. Where isolation is deemed necessary, it should be limited to a maximum of 15 days. Indefinite and prolonged solitary confinement, the kind that Richard was subject to, can in some cases be considered torture, the UN said. It also places the prisoner at increased risk of suicide.

Earlier this year, U.S. President Barack Obama banned solitary confinement for juveniles in the federal prison system. He said it can lead to devastating psychological consequences, and should be applied – for any prisoner – only as a last resort. The President said inmates should be housed in the “least restrictive setting necessary,” and, where segregation has proved necessary, institutions should develop plans to return the segregated inmate to a less restrictive setting as soon as possible. For inmates who are segregated for their own safety, the Federal Bureau of Prisons has been ordered to build reintegration housing that is less restrictive than segregation.

“How can we subject prisoners to unnecessary solitary confinement, knowing its effects, and then expect them to return to our communities as whole people?” President Obama wrote in an op-ed piece published in the Washington Post. “It doesn’t make us safer. It’s an affront to our common humanity.”

In Canada, the 2013 coroner’s inquest into the death of 19-year-old Ashley Smith, who died in custody after spending significant time in solitary, recommended that indefinite solitary confinement be abolished, and that long-term segregation of more than 15 days be banned. The Conservative government of Stephen Harper resisted those recommendations. When Prime Minister Justin Trudeau took office, he directed Justice Minister Jody Wilson-Raybould to implement the Smith inquest’s recommendations on restricting the use of solitary confinement, but so far the status quo prevails.

Mr. Sapers, the Correctional Investigator, has said that the system locks indigenous prisoners in solitary at a disproportionate rate. He has also said that administrative segregation, which is usually applied to those who pose a security risk and is different from the disciplinary segregation imposed on rule-breakers, should be capped at 15 consecutive days, and 60 days total over the course of a year.

“Segregation in my opinion has been used as a default,” Mr. Sapers told The Globe and Mail. “When it’s just too much trouble, the easier answer is to isolate the problem … Even if somebody is going to be on a modified or restricted routine, it doesn’t have to be the full 24-hour-a-day lockup, seven days a week. There’s very little good that can come out of that kind of custody.”

"You start thinking more along the lines of ‘maybe this is it, this is how I’m going to end it.’ ... Probably one of the main things down here is suicide, when somebody wants to hurt themselves."

Audio: Wolfe explains how thoughts turn to suicide in solitary.

Mr. Sapers says there are options that are more restrictive than free movement and association, but fall well short of 23-hour segregation. Over the last year, he says, the federal Correctional Service has reduced the number of inmates in segregation from a daily average of about 800 to about 500, all without legislative change.

“They’ve simply paid more attention to pursuing those options,” he says. “Clearly, when there’s a will, there’s a way.”

Richard was being held in administrative segregation in the provincial system, which is where offenders on remand who are awaiting trial are jailed, as well as those serving sentences of two years or less. The extent to which segregation is used in the provincial system is not well known, because provinces are not subject to the same reporting regulations as are the feds. The Globe found earlier this year that only one province – Quebec – could provide data on the number of inmates who had spent more than 15 days in isolation over the previous five years.

Neither Mr. Sapers nor Prof. Shalev have heard of a regime like the one Richard described at Regina, where segregated inmates do not go outdoors and instead use a fresh-air room. “That really does run contrary to international law and any form of common sense. That’s extremely unhealthy and illegal,” Prof. Shalev said.

Asked about this practice, which falls short of the UN’s Nelson Mandela Rules, also known as the standard minimum requirements for the treatment of prisoners, the Saskatchewan Ministry of Justice said all inmates are entitled to one hour of daily outdoor exercise – subject to safety considerations. A spokeswoman said, in response to written questions The Globe and Mail that took more than a month to answer, “fresh-air rooms ensure that inmates have access to fresh air in their units rather than depending on the availability of staff to escort and monitor outdoors. The fresh-air rooms also allow staff to supervise the entire unit including inmates who are participating in the exercise program in the fresh-air rooms.” She did not directly confirm the conditions of Richard’s detention as he described them, citing privacy rules.

The Saskatchewan ombudsman’s office said that it has received a similar complaint about a lack of outdoor exercise for segregated inmates in Regina, suggesting that Richard’s is not the only case.

‘You’ve got to cut deep’

Richard was at a low point by the summer of 2014. He had been in solitary for a few months, and the gravity of his situation had set in. The conditions ate at him. Meanwhile, the world outside spun further from his grasp. His girlfriend started dating someone else, and the visits with his son were increasingly rare.

One morning, he went to the shower room and, as usual, received a disposable razor from the guard. He shaved, and before returning the razor to the disposal bin, he snapped off the blade and concealed it between his fingers. “You can break a piece off and put the razor back together and give it back to them. They sometimes don’t even bother looking at it, just throw it in the garbage,” Richard explained to me later. “You can put it in your mouth or just put it in your fingers and hang onto it. I put it in my fingers.”

When he returned to his cell, he was despairing.

“You do a lot of thinking when you’re down here. Thinking from good to bad to worse,” he said later. “The bad thinking is that I’m not going to see my boy for the longest time. The worst is ending it.”

A disproportionate number of inmates commit suicide in segregation, according not only to the UN but to Canada’s correctional investigator. Richard claimed there were 15 to 20 attempts in his first year on the seg unit.

Sitting down on the cement floor, and leaning back against his bunk, he pulled the razor blade from between his fingers. He had spent enough time in prisons to know how this was done. He just wanted to go to sleep and never wake again.

“You’ve got to cut deep,” he thought to himself.

Richard paused and looked at one of the few possessions he was allowed: a photo of his son, three years old, with wispy hair and smiling eyes. He thought of his own childhood in Winnipeg, growing up without a father. He didn’t want to force the same fate on his boy. But could he muster the strength to persevere?

Minutes passed. Finally he realized that, if he took his own life, he’d be hurting his son, too, which he couldn’t bear. He hid the blade away and managed to get through that day, and then the next. He found that if he kept his thoughts on his son, he could go on.

“I’m working my way back to him,” Richard told me later. “I’m going to do my best to stay alive for my son.”

Through the fall of 2014, as he awaited his trial, the threat of being labelled a dangerous offender hung over Richard. This was the third time he had been accused of a violent crime. If a judge ruled against him, it would mean he could be held in prison indefinitely.

"I sleep more than I am up. After lunch I’m going back to bed. Just to get away from these friggin’ – to get away from reality I guess"

Audio: Wolfe describes his sleeping habits.

As the end of his first year in Regina approached, he hoped he would soon be out of segregation, or transferred to a federal prison where conditions would be better. “I’ve been 10 months on this 23-hour lockdown! I’ve seen other inmates try to take their own lives when they been down here for 30 days to 60 days,” he wrote to me.

Of the 30 suicides in the federal prison system between 2011 and 2014, nearly half – 14 – took place in segregation, the most heavily monitored cells in the system.

On March 9, 2015, Richard entered the courtroom in Regina wearing a black shirt, black jeans and glasses. His dark hair was tied in braids and the bright pink lips tattooed on his neck were just visible above his collar. He looked pale and haggard. A sheriff placed a plastic cup of water before him, and Richard reached awkwardly for it, lifting both of his shackled hands to drink. He gave me a quick nod as he hunched forward, nervously biting his lip.

Richard’s mother, Susan Creeley, sat in the front row, praying silently, her eyes fixed on the judge. Proceedings began and, almost immediately, Richard rose to say that he wanted to change his plea of not guilty. The judge asked how he wished to plead. Richard let out a croak, as the word stuck in his throat.

“Mr. Wolfe, you’re going to have to put that on record,” the judge said.

“Guilty,” he said.

The facts of the case were read into the record, an awful litany of sexual and physical violence against friends who had, out of kindness, taken him into their home. The female victim was left traumatized by the sexual assault, and the male victim walked only with the help of a walker, after being hit more than 30 times with a baseball bat, the Crown said. Richard’s shoulders slumped as the events of that night were recounted.

His lawyer requested that a Gladue report be prepared ahead of sentencing. A Gladue report is a provision, mandated by the Supreme Court, that requires judges to take into account the circumstances surrounding the life of an indigenous person before passing sentence. Named for the case of Jamie Tanis Gladue, an indigenous woman who pleaded guilty to killing her husband, such reports have been enshrined in law since 1999.

But despite the gross overrepresentation of indigenous offenders in the justice system in Saskatchewan, none of the officials in the courtroom that day – the Crown, the defence or even the judge – displayed much experience or knowledge of Gladue reports or how one might be produced.

“I really know very little about who does these reports, or how long it may take,” the Crown lawyer said.

“Who makes these arrangements, do you know?” the judge asked.

“I confess I’ve never asked for one before,” Richard’s lawyer replied.

If a report was to be ordered, Legal Aid would not pay for it, according to Richard’s lawyer. So who would? Court was adjourned to allow the lawyers to look into what should have been a basic component of sentencing in a province that has the second-largest proportion of indigenous people in the country.

Meanwhile, the delay meant Richard was going back to segregation in the provincial jail, where resources and programs are scarce, for several more months, a fact that no one mentioned that day.

Richard’s trip to court was the first time he’d set foot outside the prison and the segregation unit in nearly a year. He got to feel the outdoors, even if it was just getting in and out of a van on a chilly, overcast winter day.

Many First Nations people describe a feeling of spiritual connection with the land, a relationship that is central to how they lived and practised their religion for thousands of years. To go so long without walking on real ground felt painful to Richard. He often stood and watched from the window as inmates did laps around the prison yard.

“I wonder how it is out there,” he wrote in one letter. “It must be nice … Looking out there, seeing the grass, seeing people walk around on it, it brings a whole new meaning to trying to cope with this. Twenty-three hours a day.”

A reflective mood washed over Richard after his guilty plea. He returned from court and sat down to write a letter explaining what it was like to be in solitary.

“Come April 9, I’ve been in the hole 12 months,” he wrote. “There are times I ask myself, ‘How do you do it?’… If you don’t keep your mind busy, you can go crazy down here. You’ll start to talk to yourself or see things that are not there. I’ve seen a lot of guys go to health care, so they can get their canteen, extra food from trays, or to watch some TV. … The only way to get over there is to cut yourself up.

“There’s one other guy that’s been down here [longer than] me. By just three weeks. He gets out in June. He talks about a lot of voices in his head and he talks to himself. He seems to be okay some days, but then he just goes off.”

Sometime in March, the inmates in segregation, fed up with the conditions, launched a hunger strike. They demanded an area where they could perform smudging ceremonies, a First Nations spiritual practice that many people perform daily. They also wanted the opportunity to purchase additional food from the canteen, as segregation inmates elsewhere could, and be given extra pillows.

The hunger strike lasted several days, Richard said, although the ministry has denied that food trays were actually refused. After a few days, one inmate tried to hang himself, Richard said, and several others slashed themselves. “It was crazy. I was hoping it would end.”

He said that, without food, he felt dizzy and ill within a day, but he didn’t want to let the others down. The inmates and jailers eventually negotiated an end to the hunger strike, he said.

There was also something dramatic going on with a pair of inmates who had been in solitary for a couple of months, and who continued to act up even after the hunger strike was settled. Richard said they had yelled and screamed and pulled the sprinklers. Now they had been placed in “baby dolls,” Richard said, the term for paper wraps that are worn instead of blankets or clothing.

“They’ve been stripped of their clothes,” he explained. “And they’ve got overtime guards sitting in front of their cells watching them” – to monitor the inmates to be sure they didn’t harm themselves.

Another inmate on the unit had seriously cut himself, but was being denied the chance to go to the sick ward. Access to the ward likely was the inmate’s goal, Richard acknowledged, but he thought that the wound was serious. It was two inches long and a half-inch deep, and there was no way it was going to heal without stitches, in his view. The inmate’s blood covered the window on his cell door.

“Apparently, one of the guards said, ‘He can fucking bleed out for all we care. He’s staying where he is,’ ” Richard relayed.

After the first two nights in segregation, and every 21 days thereafter, a designated internal panel reviews the status of segregated inmates. Richard said he never raised an objection to being held in segregation to this panel, and often didn’t attend his own hearings.

“They pretty much say the same thing, either that or I don’t get called to them; they just do it without me,” Richard said. “I usually get the paper saying that I’m fine down here and I haven’t asked to move yet and I’m still high-profile.

“I really haven’t asked to move ’cause it’s [calm] down here.”

Nor did he raise a fuss about being kept inside under the “fresh-air room” regime. That’s common, according to Mr. Sapers, as inmates are often loath to complain or draw attention to themselves for fear of some form of retaliation.

Just when it seemed Richard was losing hope, he mentioned some good news: He had been given the cleaner’s job. That meant he could get out of his cell three times a day to deliver the meals in the seg unit, an additional two hours or so out of his cell every day. It was a huge boost, a gift conferred by the guards, that meant he would become the crucial social link for everyone on the unit, the one person other than their jailers they could be guaranteed a chance to speak with every day.

Richard had held the cleaner’s job before, but lost it after he failed a drug test. He had been trading extra food rations for another inmate’s prescription Ritalin, used to treat attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Richard said he liked the way it intensified his focus and improved his reading and letter writing. But now that he had the job back again, he wasn’t going to risk losing it.

One of the highlights of his day was the chance to play cards. Often Richard would sit cross-legged in front of an inmate’s door and the game would proceed, with cards sliding back and forth under the door for a half-hour or so as they carried on a conversation. Those card games were about as good as it gets in segregation, Richard said.

In federal segregation, inmates are allowed to have televisions, and, often, antique video-game systems such as the Nintendo 64 or PlayStation. Not so in the provincial system, where the radio is the only modern diversion. Radio was his constant companion, Richard said: “It has only three channels to listen to. A native channel, country and a rock channel. It stays on pretty much 24/7. I even sleep with it on so it’s not so quiet.”

The voices emanating from that dial were his most immediate connection to the outside world. Richard’s favourite part of the week was listening to news about the lottery. He daydreamed about what he would do if he won, floating for a moment on thoughts of travel, wealth and happiness: First, he’d take anyone who wanted to join him to Niagara Falls. Then he’d buy new cars and trucks for all his family members, before settling into a life as a landlord, buying apartment buildings, renovating them and renting them out (when he was free, he loved to watch real-estate television).

Richard also read a lot, but he tried to ration his reading because he was afraid he’d run out of decent books, given the limited selection. His favourites were thrillers written by Chris Ryan, the former British Special Forces operative and author of Osama and Hard Target.

In September, I made plans to visit Richard ahead of his sentencing hearing.

I drove east from Regina, following the pleasant, tree-lined road that runs to the jail. A modern facility appeared from behind the trees, its open spaces fenced off with razor wire and monitored by plenty of security cameras. I looked over the surrounding countryside, trying to picture Richard’s younger brother, Danny, sprinting across these fields when he broke out in 2008. After being buzzed in, I walked up to an empty waiting room, unsure what to do. Signs warned that I was on camera; posters and stacks of brochures invited me to join various support groups.

After a few minutes, a guard arrived. We chatted as he checked a computer file, from which I could see I was only the third person on Richard’s visitor list. The guard pulled out a large set of keys and showed me through the first locked door, where I deposited my phone and notebook in a locker.

The jail was clean and utterly silent, save for the sound of footsteps and doors locking and unlocking. The guard led me down a corridor to a row of grey plastic chairs, arranged in front of high windows. I could see Richard standing on the other side with a guard at his back. His hands were in bright yellow handcuffs and he was dressed in orange prison clothes.

He smiled and raised his hands in greeting. We sat down and said a muffled hello through the voice screen at the base of the glass. Richard’s hair was streaked with grey, and he looked older and smaller than when I’d last seen him. On the cusp of 40, he had already suffered two heart attacks: the first after he heard of Danny’s escape; the second, a few years later, after he returned to Winnipeg for the first time as a free man. After the first attack, four stents were inserted to keep the blood flowing around his heart, and he got five more stents after the second. He did not look well.

He hadn’t been sleeping, he said. He was nervous about the next day’s court date. The danger of possibly returning to general population in another facility was driven home a few weeks earlier when a guard accidentally allowed a second prisoner out of his cell while Richard was in the hallway. It happens occasionally, although it shouldn’t, and the inmates refer to it as getting “double-doored.”

The inmate threw his T-shirt over Richard’s face and started swinging. He caught Richard with a right hook. Richard staggered back, but he managed to land a few blows of his own, he said. Afterward, Richard nursed a sore jaw that kept him from eating properly for a while.

“I’ll ask to see the doctor in a few weeks to see if it’s broken. I can eat little things and talk okay. But to eat bigger meals is a bitch,” Richard wrote at the time. “I know it won’t be my last [fight]. I just have to be careful when someone pulls out a knife (knock on wood) and, hopefully, it doesn’t come to that.”

Richard sat back in his chair, matter-of-factly explaining to me that the threat of violence was ever-present in prison. One of the primary purposes of gangs inside, the Indian Posse included, is to provide inmates with some sense of protection. Richard, though, was “playing the lone wolf,” as he put it, trying to make it on his own.

Weapons are constantly being fashioned and concealed, he said. He described how at night, in segregation, you can hear the repetitive sawing sound of shanks being sharpened, particularly when someone’s getting ready to return to general population. Shanks are often made from bits of plastic that inmates gather and then bind or melt together to make them stronger, he said. Another trick is to gather chips of peeling paint and roll them into a ball. When the ball is big enough and sufficiently heavy, it can be slipped in a sock and used as a club.

Richard was obviously concerned about the danger. He talked about “the vest” – the stigma of being a sex offender – he was going to have to wear from now on. Due to his sexual-assault charge, he expected many inmates would shun him, give him the silent treatment, or even feel obliged to target him. The inmate who had attacked him suggested as much after their fight, Richard said: “He wrote me a little kite saying, ‘Don’t take it to heart.’ He was trying to make a move on me because, if he doesn’t, when he goes back to general pop, everybody’s going to look on him different.”

Richard wanted to talk about the old days when he was a teenager and a leader in the Indian Posse. I had heard most of these stories already, but he wanted to tell them again. I asked when his son had last been to visit. It had been a while, and it looked as though it pained him to consider it.

He showed me how his son would stand on the ledge, peering in at him, and then hide behind a partition, laughing. He said his son’s mother would sit to one side and watch, expressionless, barely able to look at Richard.

“Man, that makes it so much harder to do the time, being a father. I tell myself, at least he’s little now; he won’t really remember, but when he’s older, man, I really want to be out, to be a father for him.”

After an hour, the guard approached to signal our time was up, and we said goodbye.

The next morning, Richard’s court appearance was over almost before it began.

He had been waiting nearly six months for this day, having fought for the right to get a presentencing Gladue report. At first, money was an issue, because he was unable to pay to have it done. Then his mother took an advance on her wages to cover the cost. But the report was ready only a day before the scheduled court date, not enough time for its findings to be included in sentencing submissions from the Crown and defence.

The judge ordered that Richard’s case be delayed again, until November, more than two and a half months later. So Richard returned to his cell, wondering how long this would continue. He really had no idea how long he might have to stay in solitary. A few days later, we spoke on the phone.

“I was frigging pissed off,” Richard said. “It is what it is, I guess.”

He wanted to have the Gladue considered because it would almost certainly help his case, and he had spent a long time speaking to a woman from Yorkton Tribal Council who had written it. “It would open some eyes to help the judge see where I came from and how I came up,” he said. “Not just being in the spotlight of being an ex-gangster and founder and all this. Cause there’s more to it than that, if the judge could just look at my background a little further.”

Richard’s first stint in solitary confinement began when he arrived at Stony Mountain, the federal penitentiary in Manitoba, to serve his first federal sentence for attempted murder, in 1996. He was 20 years old, a vulnerable age to be placed in long-term segregation, and was kept there for months as he waited to be transferred to a maximum-security prison in Edmonton, he said.

After he arrived in Edmonton, he was stabbed in a gang hit, and wound up in segregation again, this time for another few months. He then moved to the federal prison in Drumheller, Alta., where, fearing he was about to be attacked, he stabbed someone and wound up being returned to Edmonton to do more time in the hole.

Around 2001, he was transferred to Collins Bay, in Ontario, where he got in trouble for his alleged role in a riot, and spent about nine months in segregation, he said. At the time, segregation had him debating whether to cut himself or hang himself, he said. Then, in 2007, he was suspected of tattooing other inmates at Fenbrook Institution in Ontario and spent nearly a month in isolation.

As he neared his 600th day in solitary in Regina, I asked Richard which period had been the most difficult. “Probably here,” he replied. “It’s been longer, and you don’t have much here.”

As hard as it was, over the 20 months Richard had learned how to survive. He was taking it day by day, a phrase he repeated like a mantra every time he called me. “It’s been a roller coaster, up and down. I really had some bad times, some bad thoughts. You just start thinking along the lines of maybe this is it, maybe this is how I’m going to end it. Suicide is probably one of the main things down here,” Richard said. “I pretty much went through that. I was going to end my life. … I didn’t think I could do it. I didn’t think I could stay down here in the hole that long.”

Getting the cleaner’s job helped him stay sane. Another of his coping mechanisms was to sleep all day. Richard said his routine was to stay up until midnight, fall asleep with the radio on for company, and then sleep until it was time to serve breakfast. After he finished handing out the trays, he would sleep until just before lunch, and then nap again after lunch, before finally waking around 4. Such a routine might sound like a hallmark of depression, but Richard saw it as a way to escape reality.

“I think I’ve changed quite a bit. I’m more quiet, more calm about things, I don’t rush through things. I’m humble. When we do have things down here, I’m really grateful for it,” he said.

In November, with the Gladue report complete, the Crown and defence made their arguments for sentencing, and the judge said she would take more time to weigh her decision. The Crown was seeking 10 years in prison, while the defence argued for 3 ½ years. Richard was sent back to segregation for another six weeks.

Then, on Jan. 8, he sat in the prisoner’s box in Regina court one last time.

The judge offered a summary of the findings of the Gladue report. It described Richard’s life, the influence on his parents of the sexual and physical abuse of the residential school, his early years of privation and hunger, and the violence and substance abuse that surrounded him in childhood. Richard said he was physically and sexually abused as a child.

The judge also described one incident that especially marked him. Richard said that, in Winnipeg, a teacher once stood him on a chair in front of the other students and pointed at his dirty clothes. Richard claimed the teacher told the children that this is why they should do their homework and get good grades; otherwise they would end up looking like him. Tears slid down Richard’s cheeks when the judge described this incident.

But the aggravating factors were considerable. Richard was on parole at the time of his latest crime and had a long history of violence. The impact of his crimes on his victims was devastating. The female victim said: “I thought we were safe in our own home. Now I’m scared to trust anyone and everyone.” From the male victim: “Richard Wolfe has made our lives a nightmare in a blink of an eye, when all we were trying to do was help him get his life back on track and keep him from his past negative ways.”

“Unquestionably, Mr. Wolfe’s background was harsh and unforgiving,” the judge said. “At an early age he learned how to steal just to stay alive. Survival was a daily struggle, and gang life was seen as a viable option.”

He was abused as a child and witnessed violence, and was a generational victim of the residential schools, the judge said, all of which modestly detracted from his moral culpability, she concluded.

She sentenced Richard to five years. He told me he expected he would again be placed in solitary confinement when he arrived at Sask Pen, the federal penitentiary in Prince Albert. Richard had a sense of foreboding about going there. It was where Danny had been murdered in 2010, a place that his younger brother referred to as “the house of misery.”

“I’ll take it one day at a time and put my back against the wall. The way I look at it, I took care of myself for 15 years,” Richard told me soon after. “I’ll just have to see what pops off when I get there.”

He phoned one last time before he was shipped north in January, because he wanted to record a message for his son, in case he didn’t make it back. He told him he loved him, told him to be a good boy and that he would watch over him.

I didn’t hear from Richard again. I was expecting his call, since a prison official phoned to tell me Richard had added me to his phone list. I wrote him a letter and got no reply, but in the past, other prisoners in the federal system have described being blocked from speaking with journalists.

Last Friday, Richard collapsed in the exercise yard. His mother said she was told it was a heart attack. The Correctional Service will say only that foul play is not suspected. A spokesman declined to say whether Richard had been in segregation, as his death and the circumstances surrounding it are subject to an investigation.

Richard Wolfe died at the age of 40, having spent nearly half his life behind bars.

Joe Friesen is a Globe and Mail reporter and author of the recently published The Ballad of Danny Wolfe: Life of a Modern Outlaw.

Commentary by the Ottawa Mens Centre

Congratulations to the Globe and especially to reporter Joe Friesen for this extraordinary article that provides a real picture of the reality of Canadian Jails.

The conditions described were at Regina, but are very similar to all Canadian Federal Jails but are far superior, a virtual holiday camp compared to Ontario Provincial Jails like the Ottawa Regional Dention Centre, the dreaded OCDC , aka the Ottawa jail.